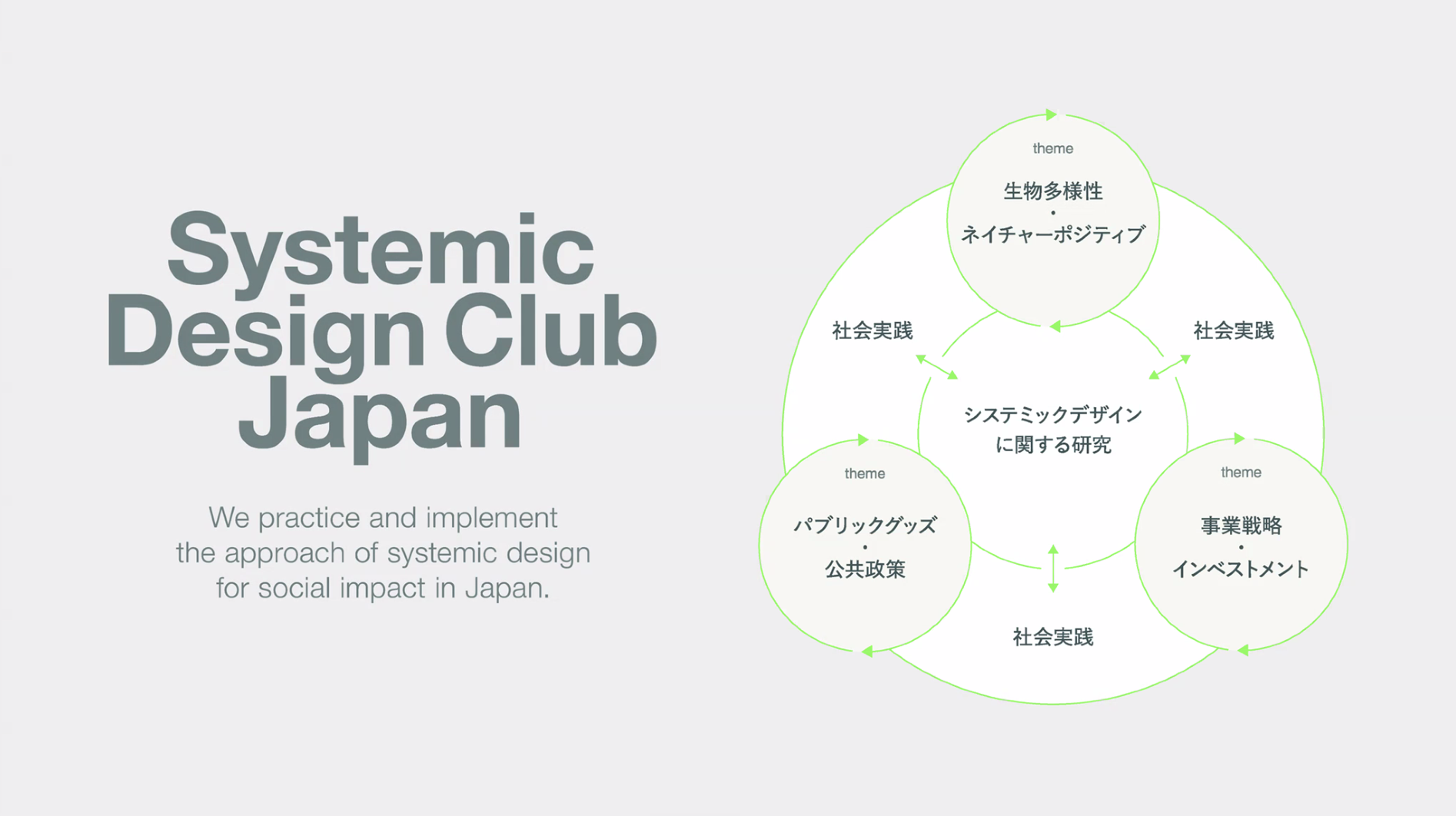

Systemic Design Club Japan

Talk

Grateful to ACTANT and Ryuichi Nambu for inviting me to speak at the Systemic Design Club Japan. It was a pleasure to engage with such a diverse group of professionals from design, policy, and finance on the topic of portfolio approach.

Below is a short summary of my presentation as well as a longer write up written by the Systemic Design Club members and the full video recording.

![]()

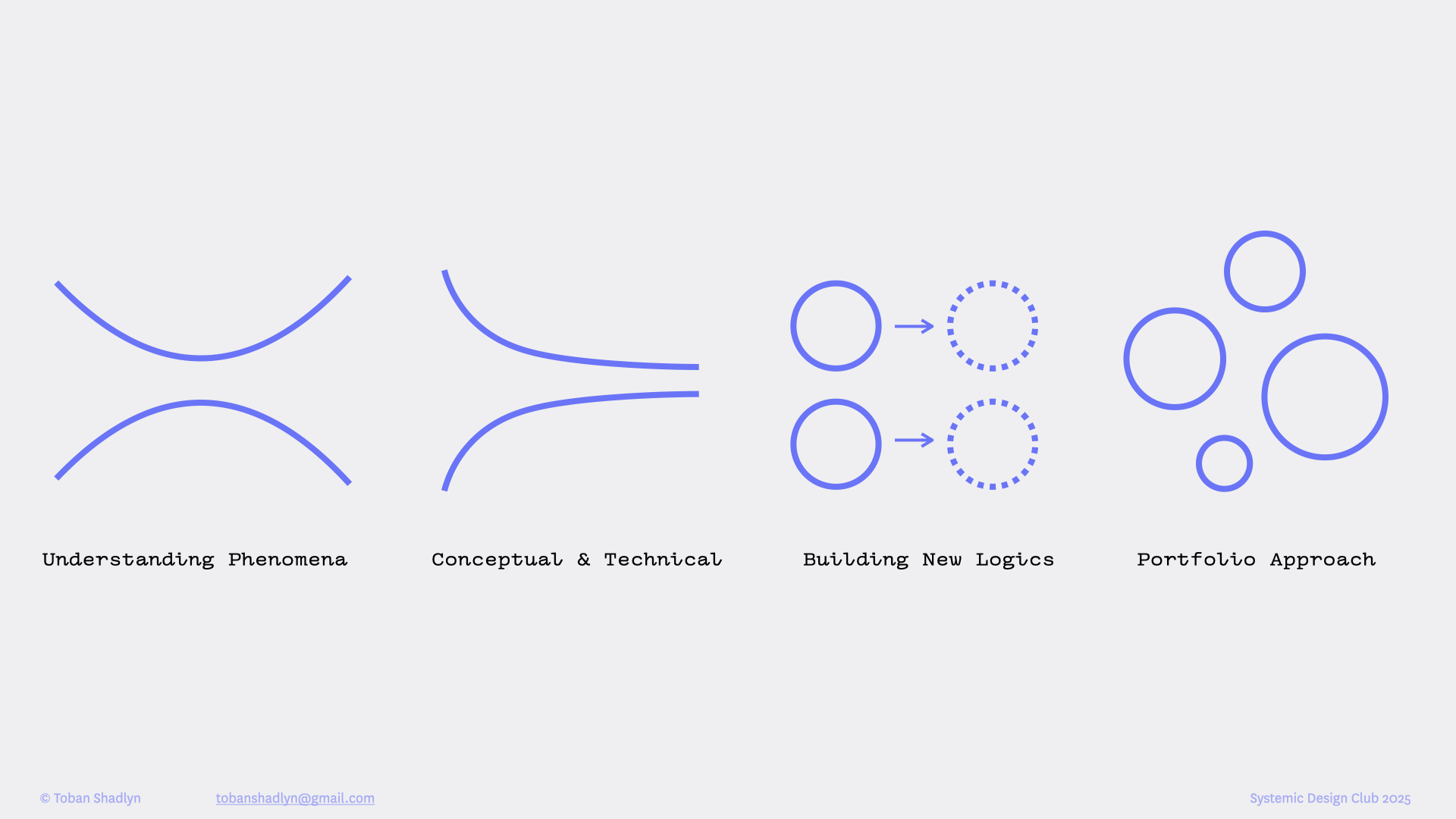

During my talk, we explored:

→ The importance of identifying the nature of the challenges we are addressing.

→ What a portfolio approach is and its usefulness in addressing complex systemic challenges.

→ Understanding the phenomena of a challenge, both pasts and presents, before designing futures.

→ Balancing work at both the conceptual and technical scales of the challenge.

→ Building new logics: not being bound by rigid structures of knowledge, but instead re-ordering information in ways that open up new ways of seeing and acting.

Below is a short summary of my presentation as well as a longer write up written by the Systemic Design Club members and the full video recording.

During my talk, we explored:

→ The importance of identifying the nature of the challenges we are addressing.

→ What a portfolio approach is and its usefulness in addressing complex systemic challenges.

→ Understanding the phenomena of a challenge, both pasts and presents, before designing futures.

→ Balancing work at both the conceptual and technical scales of the challenge.

→ Building new logics: not being bound by rigid structures of knowledge, but instead re-ordering information in ways that open up new ways of seeing and acting.

A few key takeaways:

The questions from the community were particularly revealing, highlighting the shared threads many of us are grappling with:

⦿ How do we resource and fund this way of coordinating?

⦿ How do we align on shared future directions? And what roles of orchestration are needed?

⦿ How are we designing time, navigating different time horizons, and orienting around them effectively?

⦿ What capacities are needed to enable systemic transformation?

It’s clear that moving toward a portfolio way of working requires rethinking roles, time, resources, and the ways we collectively make sense of complex challenges.

Systemic Design Meetup

Presentation Summary

Written by Nambu and Teruki. This has been translated into english from the original version in Japanese.

Presentation Summary

Written by Nambu and Teruki. This has been translated into english from the original version in Japanese.

Systemic Design Meetup 2: Serious systemic changes

On September 16, 2025, we held "Systemic Design Meetup #2 - Learning from Practical Examples: Serious Systemic Changes".

This time's guest is Toban Shadlyn, a designer who teaches at ELISAVA, a design school in Barcelona, and works on projects related to social change around the world. Toban, gave a presentation on "portfolio approach", a concept that was introduced in the last meetup.

This time, we shared from the perspective of practitioners who have incorporated the portfolio approach through projects they have been involved in so far. In this article, we will introduce the contents a little deeper.

You can also see the full lecture (in english) in the video below.

Overcome the "Story of Separation"

“We are at the limits of expired or expiring stories”

- Vanessa Machado de Oliveira

Inspired by Vanessa’s words, Toban added to this sentiment stating “we are now at the limits of the ‘story of separation’”. Toban said that in order to understand the challenges of the 21st century and work on solving them, we need to re-examine how the systems, structures, and logic we have built in the 19th and 20th century have been formed.

For example, schools, hospitals, and prisons - these systems have been designed under a hierarchical and divided system that values efficiency and control. Just as the boundaries on the map separate people from nature, we have created a society on the premise of “separation” even in cognition.

Diagram of the Federal Government and American Union 1862.

Diagram of the Federal Government and American Union 1862. However, such structures and logic can no longer cope with the current complex challenges. That's why we need to spin a “new story that overcomes separation”, says Toban.

“Although humans are an extension and part of this planet, there is a story and logic that humans are separated from this planet. However, social systems based on these separate paradigms can no longer effectively respond to complex challenges. That's why we need different stories, different logics, tools, and approaches.”

Live with the Dancing Landscapes

Modern social issues cannot be explained by a simple relationship between cause and effect. Using the metaphor of complexity scholar Scott Page, Toban described that different issues can be understood as different “landscapes”.

First of all, “Simple Landscapes”. Challenges where the task is quite simple, aka it is clear where the top of the mountain (solution) and the way to climb it is known (method/approach).

Next, “Rugged Landscapes”. Challenges that are complicated and difficult to understand, not clear where the highest peak is (solution), and will take time to find the right path to it. For example, vaccine development, it is a type of issue that can reach a final solution while various factors are involved.

And another one is “Dancing Landscapes”. The context itself is constantly changing, and every time we intervene, a new movement is created. Many social issues in the 21st century - climate change, AI, health, etc. - fall under this “dancing terrain”.

The situation is constantly changing, and the intervention itself changes the environment. In order to respond to such a fluid reality, an experimental and adaptive approach such as a portfolio approach is required, rather than setting fixed goals and solutions.

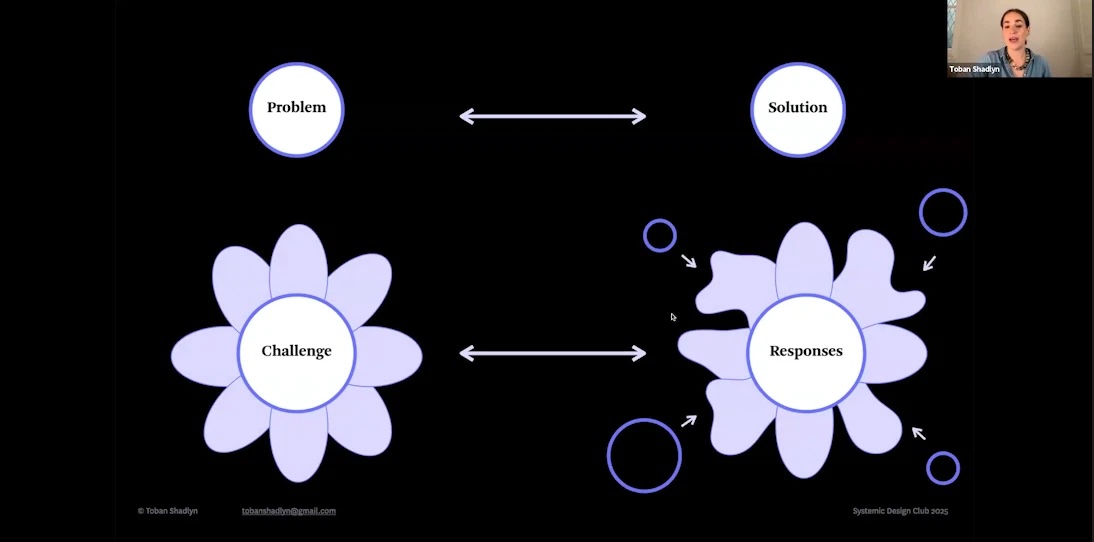

As shown in the figure below, complex challenges need to factor many things (visualized as petals). This requires a diversity of actors to engage as one expert, one organization, may only look or be “responsible for” one petal.

On the premise that the issues continue to work together and move dynamically, we will cooperate with a wide range of ecosystems to incorporate multiple perspectives, multiple methods, and multiple time axes into strategies and actions. It is necessary to acquire such different abilities as before, personally, organizationally, and collectively.

“A portfolio approach can be said to be a collection of interventions that work together to deliver strategic results. Those interventions are an important factor that enables the transformation of reality towards desirable futures. The portfolio defines the broader map of where we are intervening and creates changes across multiple layers and multiple time axes.”

Changes that Begin With Re-looking at the Past

Toban emphasizes the importance of “understanding the past” before making change.

It is not only the visible system that drives the structure of society. Behind it is the mental models (frameworks of thinking) that we naturally believe in. What kind of mental models have we inherited and are operating from? Toban argues that in order to address many of the systemic challenges, it is necessary to re-examine our mental models, to assess if they are serving us or not. And if not, to update them.

“Before we move forward and start designing different futures, it is essential to pause, change direction, look back, and understand the logic and culture of the past and present. What have we inherited and what do we need to let go of?”

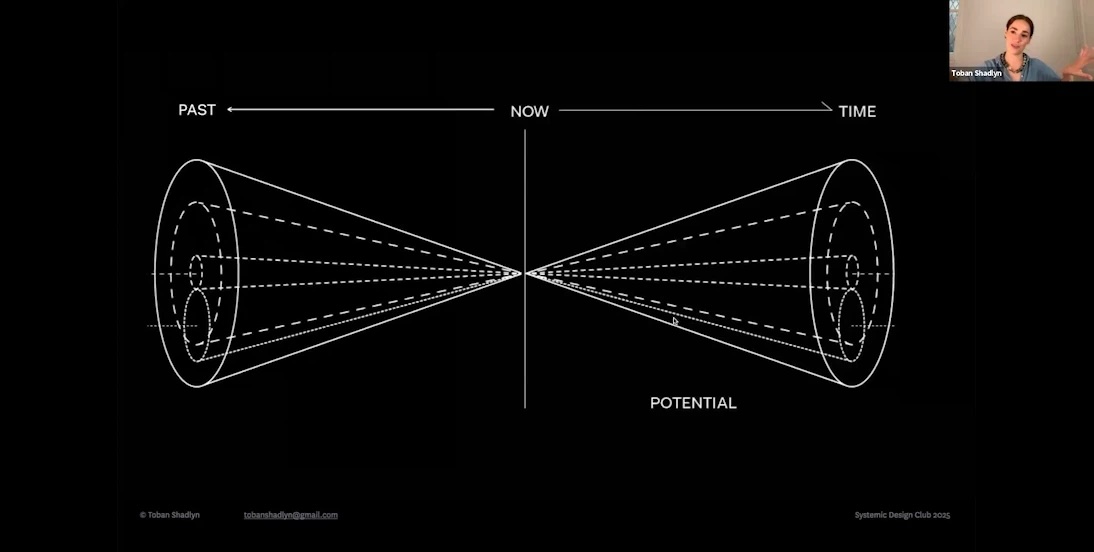

Futures Cones diagram projected forward and backwards

In addition, Toban emphasizes that looking to the past—at histories and lineages—is a vital way to think about a portfolio of interventions. Humans often focus their energy on ‘starting something new’, ‘building from scratch’, but this may limit the possibility of considering what interventions might be necessary and where they may sit to support transitions and change. For example, some inteventions may play a role in ‘winding down or hospicing existing narratives, behaviors, or organizations’ rather than ‘launching something new’. This approach calls for awareness of multiple perspectives and time scales.

The Berkana Two Loops Model. Diagram is re-drawn by Commonland.

The Berkana Two Loops Model. Diagram is re-drawn by Commonland. Practice in Rhode Island: Rewriting the story of drug use

Toban introduced the drug overdose countermeasure project in Rhode Island, USA – work she was involved in for years –as an example of practicing a portfolio approach.

Historically, in the United States, drug use was considered a personal moral defect, and as a result of this narrative, a system was created that deemed drug use a crimial matter. The resulting policies (such as the “War on Drugs”) have cast a long shadow over society, leading to the unjust detention and disproportionate incarceration of people of color.

To develop a deeper understanding of this reality and how it manifested in the present in the context of Rhode Island, Toban and her team participated in local events and public meetings for months, building relationships with people from various positions, including medical professionals, people who use drugs, researchers, policymakers, and local community-based organizations.

The goal was not to propose or develop an immediate solution but to understand “the readiness of the ecosystem”, in other words how and if Rhode Island was ready to engage with change. As her team continued dialogues and small experiments in the state, relationships were strengthened and activities spread like a snowball.

Little by little, Toban and her team began to de-veil these existing mental models like “drug use = individual defect” surfacing that this is a flawed way of understanding – what they call an “epistemological error”. And that actually we need to shift this understanding away from one that is based off of moral judgement and towards one that more accurately represents the biological reality that “addiction is part of the nature of human beings”. Other examples of these epistemological errors include shifting from “treating dependence as a crime towards a health and welfare issue”. These changes in perspective and understanding were the beginning of new stories.

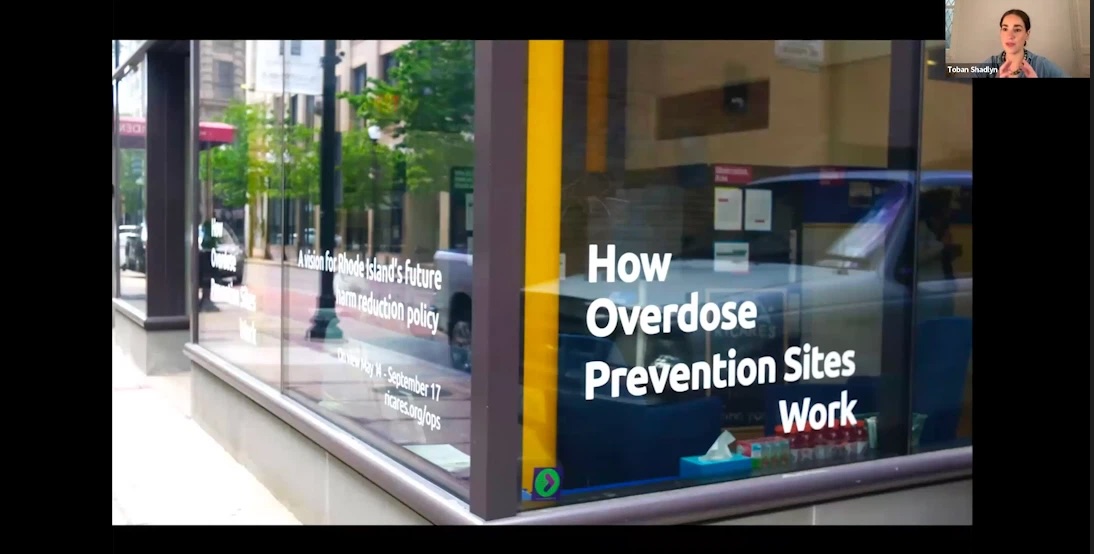

From these changes, various projects have been created in Rhode Island, such as a manifesto to depict the “future of a caring system”, passing new legislation making safe injection sites legal, becoming the first state in the US to do so and opening the first state sanctioned one in December 2024.

How Overdose Prevention Sites Work exhibition, developed in collaboration with Toban’s team at RISD Center for Complexity, Brown Public Health researchers, and community-based harm reduction group RICARES. This exhibition invited the public to experience what exactly a safe injection facility is and does. This travelled around Rhode Island and Massachusetts, eventually leading to legislation reform.

Toban emphasizes that these processes were never planned from the start and were not linear. It is not something that can be clearly defined as it was only realized because her team remained involved, and that it is important.

“As you can imagine, it is very difficult to track and measure the results and effects of all this work. I can't say for certain that ‘we did this...and that's why this happened’. It may be similar to a loose correlation. ‘We did a lot of things with a lot of people, and the situation began to change over time.’”

Cultivate Change with Time

A question from the audience, “How do you get funds for activities that do not have such a definition of results and a specific path?”.

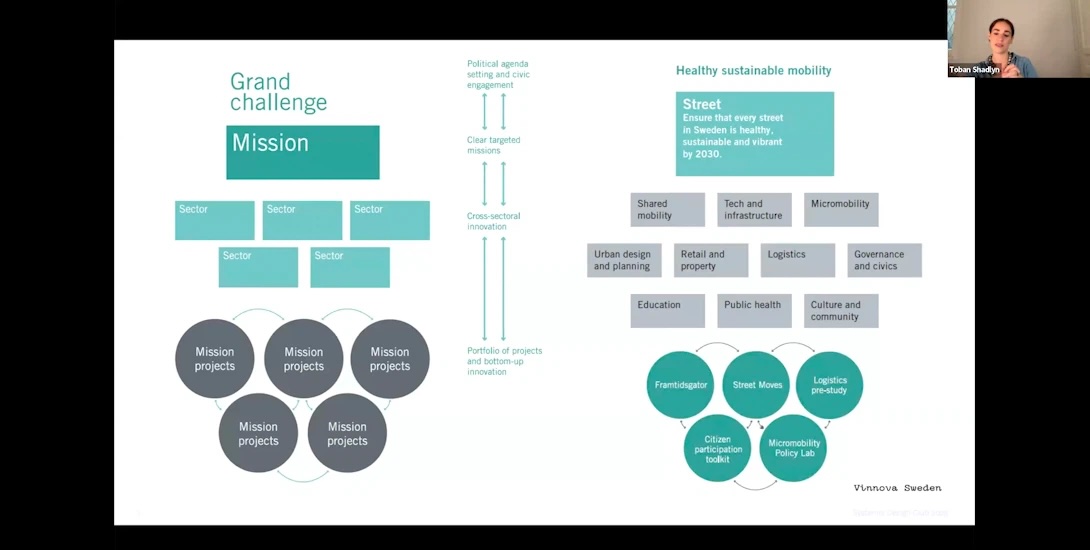

Toban offered different examples, including the case of the Swedish government’s innovation agency Vinnova, whose mission is to promote and strengthen innovation and sustainable growth. In such an environment, Vinnova itself practices a mission-driven approach similar to the portfolio approach, and plays a role in involving different stakeholders, coordinating interventions, and setting the first spark.

Images from Vinnova’s Designing Missions Handbook.

On the other hand, in Toban's own project, it began with a collaboration with a company that shares the desire to do something about the challenge of drug overdose, and as the activities gradually expanded, various sources of funding such as national sources were accessed.

“As we spend more time in the space, as we become more active, as we meet more people and organizations, as time goes by, there is more room to think about how we can raise money for these efforts.”

And what Toban emphasized in this lecture in particular was the perspective of how to incorporate ‘time’ into the process. Social change can take 10 or 20 years (and longer). It is said that it is important to assume its long-term nature in advance and to find funders and colleagues who align with it.

“We aim to create a place for change, not an immediate result.”

To End

Finally, Toban presented three questions about making a change: 1) Roles, 2) Resourcing, 3) Time.

While going back and forth between these three, “what kind of roles are necessary?” “how to secure different kinds of resources?”, and “what kind of time axis to proceed?”, continuing to ask about these are key to making systemic changes a reality.

Until I heard Toban’s story, it seemed that the first thing to do in the practice of the portfolio approach was to prepare plans and conditions, such as involving stakeholders in a wide area and broadly identifying intervention measures, but this lecture, what I saw through it, was rather the opposite.

First of all, create a small but specific output, and stack the hitting moves according to the situation. It is the accumulation of such steady practice that grows the germ of change.

Take your time, carefully, and sometimes muddy. While dancing together on the ‘dancing terrain’, we create the necessary changes. We need flexibility as an attitude and in the way funds and ecosystems support this way of engaging. It was a time to be deeply encouraged by Toban’s straightforward practice.

Editorial Notes

Due to time limitations during the talk, I’d like to add additional context about the U.S. opioid crisis. My remarks in the recording did not fully capture the accuracy of the crisis. The U.S. is currently in its third wave of the modern opioid epidemic. The first wave began in the 1990s, when pharmaceutical companies aggressively promoted prescription opioids while minimizing addiction risks, leading to widespread prescribing and dependence. As medical awareness grew and prescribing declined, many people who were already dependent turned to illicit opioids, particularly heroin (second wave). Over time, the illicit drug supply became increasingly dominated by fentanyl and other synthetic opioids (third wave), creating a highly unpredictable and lethal market in which people often do not know what they are consuming, driving today’s overdose crisis.

Index