Rebel Roots

Project

Today’s food system feels like a conveyor belt, feeding us the same handful of foods over and over again. Supermarkets prioritize what lasts longer on the shelf, looks perfect, or ships well, not what tastes incredible. Somewhere along the way, many of us have lost the connection between the food we eat and the land, people, and stories behind it.

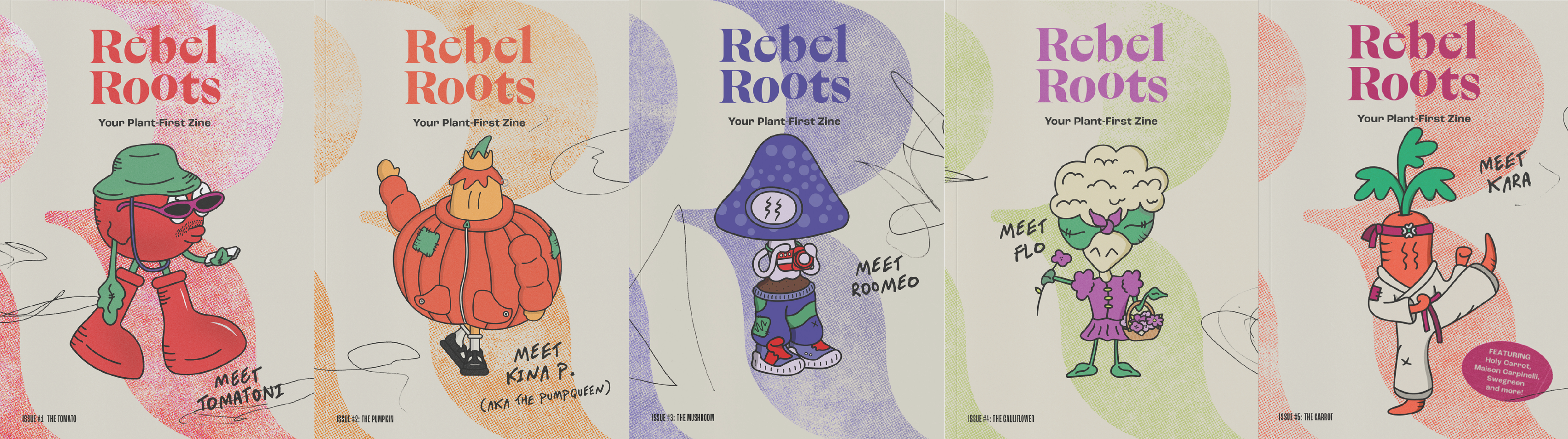

Rebel Roots began as a globally distributed, plant-led food magazine — with each issue spotlighting a single vegetable as a cultural, ecological, and nutritional protagonist. We use the magazine as a tool for dialogue, bringing together chefs, food systems specialists, and impact-driven businesses to bring visibility across the food systems. What started as a storytelling project has since evolved into a broader mission: to reconnect people with the roots of what they eat and with each other.

Rebel Roots has expanded beyond print, organizing activities and events to engage with a range of stakeholders around the food system.

Rebel Roots began as a globally distributed, plant-led food magazine — with each issue spotlighting a single vegetable as a cultural, ecological, and nutritional protagonist. We use the magazine as a tool for dialogue, bringing together chefs, food systems specialists, and impact-driven businesses to bring visibility across the food systems. What started as a storytelling project has since evolved into a broader mission: to reconnect people with the roots of what they eat and with each other.

Rebel Roots has expanded beyond print, organizing activities and events to engage with a range of stakeholders around the food system.

Rebel Roots Magazine Issues

Beyond the Bite

Rebel Roots received a small grant from EIT FoodUnfolded® to develop a series of public events encouraging food system awareness and curating the copious amounts of information available into tangible action items.

The grant helped us convene diverse communities, activate knowledge into action, and build space for agency: not just talking about food system transformation but practicing it, socially, relationally, in real time.

Barcelona Design Week, October 2025

About the exhibition: Beyond the Bite

In today’s urban world, many of us feel cut off from our food: where it comes from, how it’s grown, who’s involved, and what impact it has. That distance can leave us disconnected, without the agency to demand change or imagine new possibilities. But food is more than fuel...it’s a relationship, a story, and a shared table.

What’s your relationship with food? What guides the choices you make about what to buy, cook, and eat?

At Rebel Roots, we’ve been connecting the dots of the food system…one vegetable at a time. This exhibition invites you to peek behind the scenes of complex food challenges and discover how knowledge can turn into action. Our goal? To empower each of us to make choices that nourish not just our bodies, but also our communities and the planet.

Step inside and meet the foods you thought you already knew. Pull up a chair at one of our dining tables and spark a conversation with a tomato, a carrot, some corn, or even a mushroom. Each has a story to tell, and together, they’ll help us reimagine our food systems.

All Those Festival, November 2025

About EIT FoodUnfolded®

EIT FoodUnfolded® aims to increase trust in food and catalyse a movement of people interested in creating the future of food together. Powered by EIT Food, a European Knowledge and Innovation Community (KIC), which receives funding from the European Commission body ‘EIT’. EIT Food was set up to transform our food ecosystem and it supports innovative and economically sustainable initiatives which improve our health, our access to quality food, and our environment.

Upcoming events

Barcelona Design Week: October 15-17, 2025, Barcelona

All Those Market: November 1-2, 2025, Barcelona

Palto Alto Festival: December 6, 2025, Barcelona

Meal Prep Workshop: December 8, 2025, Barcelona

The grant helped us convene diverse communities, activate knowledge into action, and build space for agency: not just talking about food system transformation but practicing it, socially, relationally, in real time.

Barcelona Design Week, October 2025

About the exhibition: Beyond the Bite

In today’s urban world, many of us feel cut off from our food: where it comes from, how it’s grown, who’s involved, and what impact it has. That distance can leave us disconnected, without the agency to demand change or imagine new possibilities. But food is more than fuel...it’s a relationship, a story, and a shared table.

What’s your relationship with food? What guides the choices you make about what to buy, cook, and eat?

At Rebel Roots, we’ve been connecting the dots of the food system…one vegetable at a time. This exhibition invites you to peek behind the scenes of complex food challenges and discover how knowledge can turn into action. Our goal? To empower each of us to make choices that nourish not just our bodies, but also our communities and the planet.

Step inside and meet the foods you thought you already knew. Pull up a chair at one of our dining tables and spark a conversation with a tomato, a carrot, some corn, or even a mushroom. Each has a story to tell, and together, they’ll help us reimagine our food systems.

All Those Festival, November 2025

About EIT FoodUnfolded®

EIT FoodUnfolded® aims to increase trust in food and catalyse a movement of people interested in creating the future of food together. Powered by EIT Food, a European Knowledge and Innovation Community (KIC), which receives funding from the European Commission body ‘EIT’. EIT Food was set up to transform our food ecosystem and it supports innovative and economically sustainable initiatives which improve our health, our access to quality food, and our environment.

Upcoming events

Barcelona Design Week: October 15-17, 2025, Barcelona

All Those Market: November 1-2, 2025, Barcelona

Palto Alto Festival: December 6, 2025, Barcelona

Meal Prep Workshop: December 8, 2025, Barcelona

Index