Designing With Drought

Academic Program

The lake-bed of the Sau reservoir, exposed by low water levels following drought, in Vilanova de Sau, Spain, on April 3.Photographer: Àngel García/Bloomberg.

The Master In Strategic Design in Complexity is a one year program at ELISAVA School of Design and Engineering in Barcelona Spain and in partnership with Kaospilot in Aarhus Denmark.

Between October-December 2023 the students of the Master or Strategic Design completed their first studio project in response to the brief – Designing With Drought: Navigating Complexity in Water-Scarce Futures.

Below is a description of the brief, the studio course, and the final student outcomes.

Between October-December 2023 the students of the Master or Strategic Design completed their first studio project in response to the brief – Designing With Drought: Navigating Complexity in Water-Scarce Futures.

Below is a description of the brief, the studio course, and the final student outcomes.

Student designed exhibitions presented at Barcelona Design Week 2024

Studio Brief

In the summer of 2022, if you were walking around the city of Barcelona, you might have noticed signs like the one below. These were part of a campaign identifying the increase of climate shelters in the city to almost 200 – a response to the record breaking high temperatures and the need to ensure safe places with access to shade and water for residents, tourists and pets alike.

![]()

Signage indicating which spaces around the city are designated climate shelters. Source: Ajuntament de Barcelona

Of course interventions like this are tied to the urgent and important challenges of the climate crisis, the impacts presently – and yet to be – felt in Barcelona as well as the wider region of Catalunya.

It is everyday signals (like the climate shelter signs), that indicate changes in our built environment, prompting new behaviours, confronting new realities, that makes us ask: How will Barcelona adapt as the city, the region, and the country all continue to get hotter year upon year?

![]() Source: BBC

Source: BBC

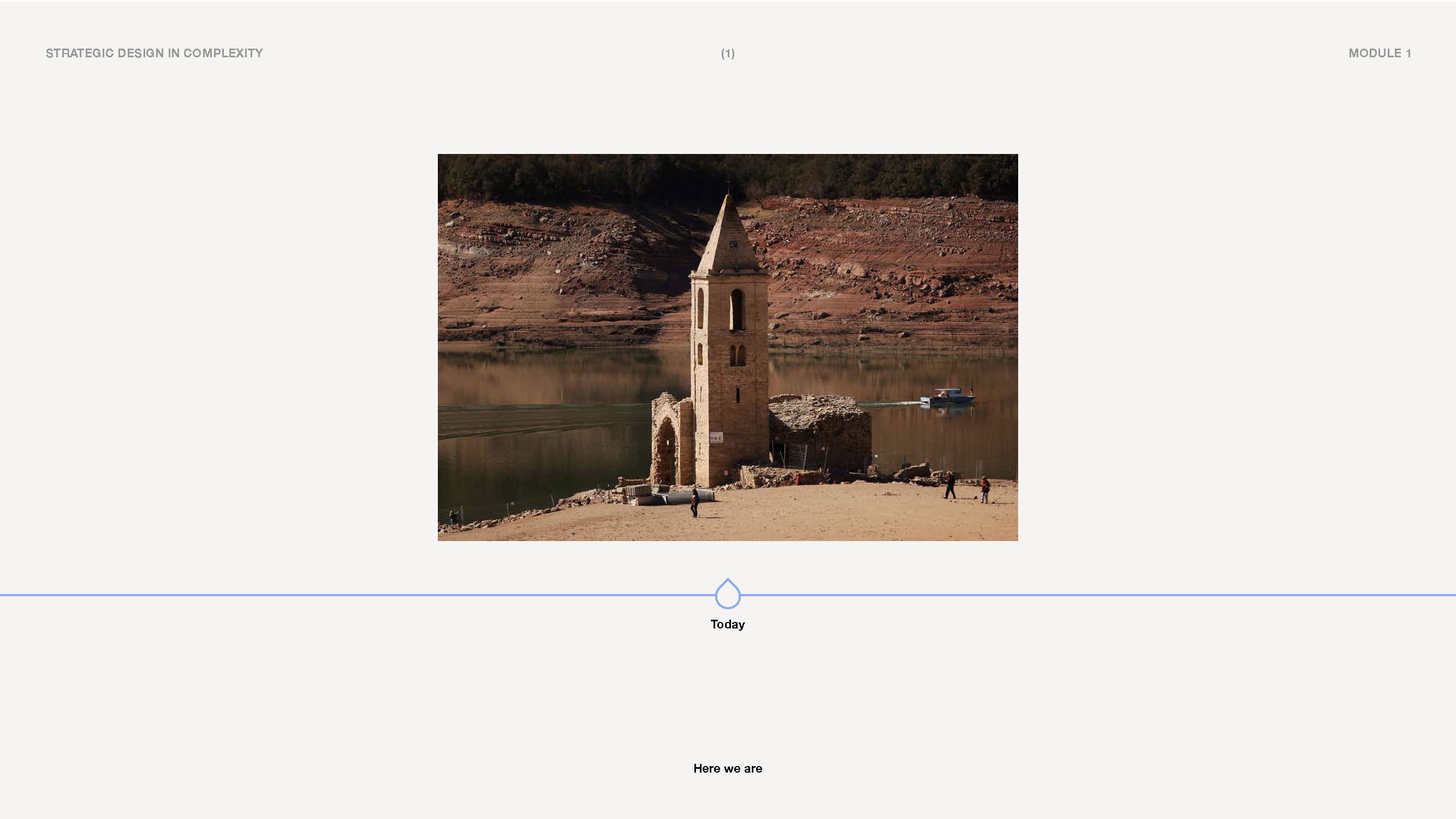

In the spring of 2023, media across Europe reported on Spain’s escalating water crisis. Perhaps the most haunting image was that of the Sau Reservoir in Catalunya. For decades, it had supplied drinking water to the region. But as drought intensified, water levels dropped so dramatically that the 11th-century church of Sant Romà de Sau, long submerged beneath the reservoir, re-emerged. An ominous monument to what’s been lost, and what’s at stake.

![]()

The 11th Century church of Sant Romà de Sau was submerged when the reservoir was created in 1962. Source: Reuters

In response, the government of Catalunya announced changes to the water usage across Barcelona and the wider region. Restrictions were placed on agricultural, industrial, and recreational use of water, including a ban on watering gardens or green areas, filling public fountains, shutting off some of the city’s public drinking fountains, and limiting personal use to 200 liters per person per day.

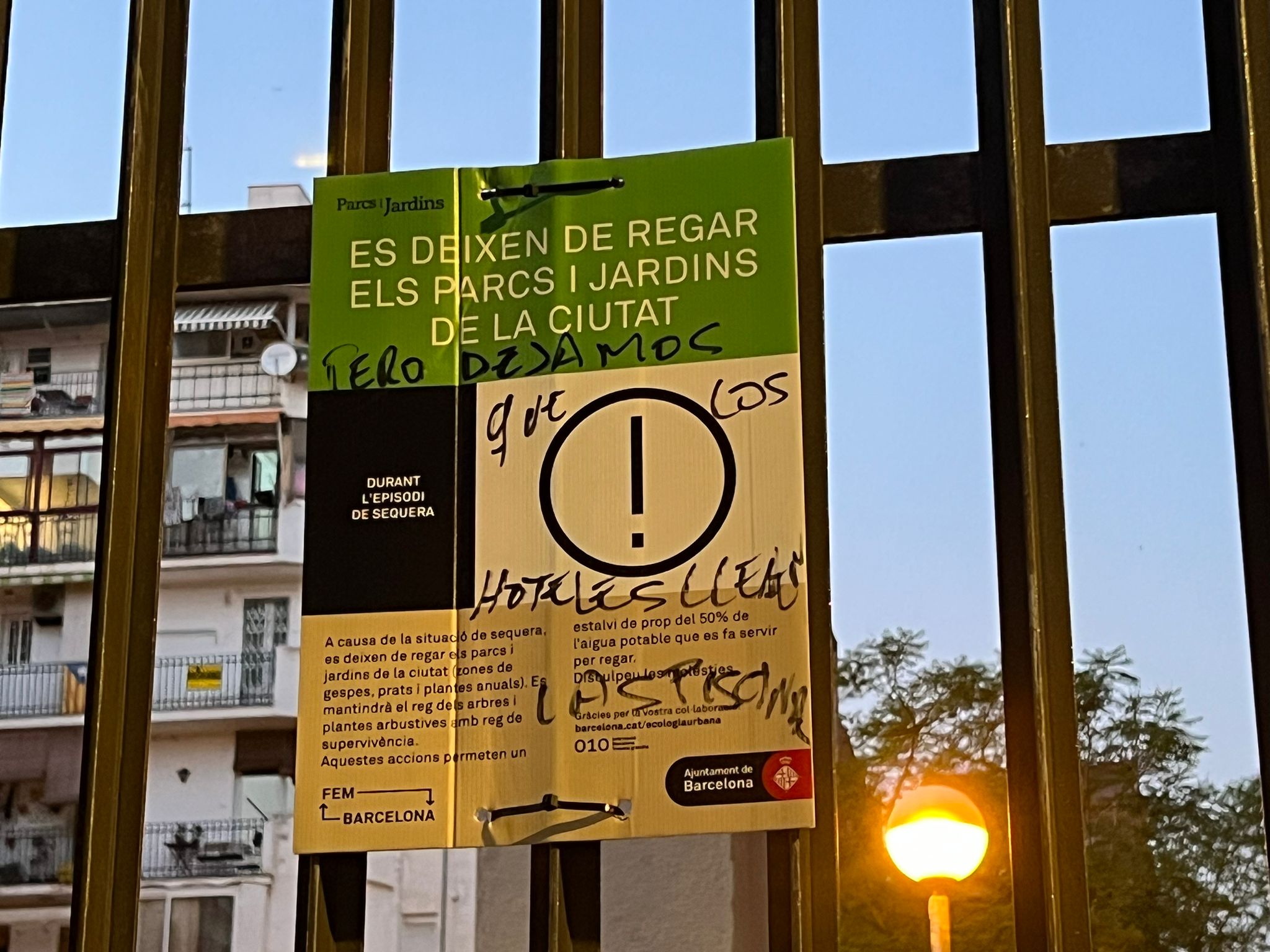

![]()

A sign outside of a park in Barcelona notifying residents that the city will not be watering the parks or gardens due to the drought situation potentially saving 50% of potable water. Source: Toban Shadlyn

As the climate crisis wavers on, how will the region prepare for a reduced availability of potable water in the context of drought? Or on the flip side, prepare for a greater increase of flooding due to unprecedented rainfall. What effects can we expect to see on the food people eat, the work they do, the communities they’re part of, the places they live, and the services which support them?

A list of key actions and responsible actors related to “Taking Care of Water” outlined in Barcelona’s Climate Emergency Declaration. January 2020.

Throughout this project, students will identify where in Barcelona current challenges exist, the evidence of how they manifest themselves already, where they are likely to arise, and the form they will appear in. Understanding the historic and present day dynamics are a vital first step in beginning to understand how potential futures may unfold, and most importantly what can be done now in the present.

Signage indicating which spaces around the city are designated climate shelters. Source: Ajuntament de Barcelona

Of course interventions like this are tied to the urgent and important challenges of the climate crisis, the impacts presently – and yet to be – felt in Barcelona as well as the wider region of Catalunya.

It is everyday signals (like the climate shelter signs), that indicate changes in our built environment, prompting new behaviours, confronting new realities, that makes us ask: How will Barcelona adapt as the city, the region, and the country all continue to get hotter year upon year?

Source: BBC

Source: BBC

In the spring of 2023, media across Europe reported on Spain’s escalating water crisis. Perhaps the most haunting image was that of the Sau Reservoir in Catalunya. For decades, it had supplied drinking water to the region. But as drought intensified, water levels dropped so dramatically that the 11th-century church of Sant Romà de Sau, long submerged beneath the reservoir, re-emerged. An ominous monument to what’s been lost, and what’s at stake.

The 11th Century church of Sant Romà de Sau was submerged when the reservoir was created in 1962. Source: Reuters

In response, the government of Catalunya announced changes to the water usage across Barcelona and the wider region. Restrictions were placed on agricultural, industrial, and recreational use of water, including a ban on watering gardens or green areas, filling public fountains, shutting off some of the city’s public drinking fountains, and limiting personal use to 200 liters per person per day.

A sign outside of a park in Barcelona notifying residents that the city will not be watering the parks or gardens due to the drought situation potentially saving 50% of potable water. Source: Toban Shadlyn

As the climate crisis wavers on, how will the region prepare for a reduced availability of potable water in the context of drought? Or on the flip side, prepare for a greater increase of flooding due to unprecedented rainfall. What effects can we expect to see on the food people eat, the work they do, the communities they’re part of, the places they live, and the services which support them?

A list of key actions and responsible actors related to “Taking Care of Water” outlined in Barcelona’s Climate Emergency Declaration. January 2020.

Throughout this project, students will identify where in Barcelona current challenges exist, the evidence of how they manifest themselves already, where they are likely to arise, and the form they will appear in. Understanding the historic and present day dynamics are a vital first step in beginning to understand how potential futures may unfold, and most importantly what can be done now in the present.

Students from the cohort engaging in field work.

The Challenge

The challenges around the climate crisis are plentiful and complex. As one entry point into this, we will focus on water as a way of exploring systemic considerations. However, simply focussing on water is still incredibly broad and you will need to define the parameters of your exploration (ie. build in constraints). You will work as a team of strategic designers exploring, reframing, and developing interventions in response to the ongoing process of the city’s strategy for water management.

The course will culminate in a final presentation, an opportunity for you all to share your work with a group of invited external guests, receive feedback, and engage in meaningful discussion.

The course will culminate in a final presentation, an opportunity for you all to share your work with a group of invited external guests, receive feedback, and engage in meaningful discussion.

Starting Considerations

What are the histories related to water in Barcelona?

How has the city managed or been designed around water throughout the centuries?

How is water managed today across the city?

Are there clues or hints that indicate how it might evolve in the next 10, 20, 30 years?

What types of water systems are controlled, owned, operated and by whom? Where? When? And How?

How does decision making around challenges related to water happen?

How does safety play a role (present or not)? For whom? How is it different for different actors (users, operators, maintainers, human, nonhuman)?

What other factors do we need to consider? (pleasure, comfort, access…)

What surrounds or is connected to different aspects of water?

What objects, services, technology, places, systems, economics, rules or policies exist to support it, maintain it, operate it, control it, communicate it?

How has the city managed or been designed around water throughout the centuries?

How is water managed today across the city?

Are there clues or hints that indicate how it might evolve in the next 10, 20, 30 years?

What types of water systems are controlled, owned, operated and by whom? Where? When? And How?

How does decision making around challenges related to water happen?

How does safety play a role (present or not)? For whom? How is it different for different actors (users, operators, maintainers, human, nonhuman)?

What other factors do we need to consider? (pleasure, comfort, access…)

What surrounds or is connected to different aspects of water?

What objects, services, technology, places, systems, economics, rules or policies exist to support it, maintain it, operate it, control it, communicate it?

How much space does it require, does it take up? Does it require more, less?

What are the repercussions or opportunities of it expanding or diminishing?

What is the effect of that on street scale, neighborhood scale, and city scale?

What kinds of challenges exist around water?

What should stay stable? What needs to be amplified? What needs to change?

How might we learn from a place’s history, culture, geography, ecology, and more to first understand and eventually enable specific, place-based opportunities?

How might we collaborate with, and enable, our living world to co-create

How might we ensure the built environment is created to last, adapt, and thrive as part of nature?

How might we work with people and place to create shared ownership, decision-making around the challenges we face and enhance collective responses to them?

What are the repercussions or opportunities of it expanding or diminishing?

What is the effect of that on street scale, neighborhood scale, and city scale?

What kinds of challenges exist around water?

What should stay stable? What needs to be amplified? What needs to change?

How might we learn from a place’s history, culture, geography, ecology, and more to first understand and eventually enable specific, place-based opportunities?

How might we collaborate with, and enable, our living world to co-create

How might we ensure the built environment is created to last, adapt, and thrive as part of nature?

How might we work with people and place to create shared ownership, decision-making around the challenges we face and enhance collective responses to them?

Students engaging in field work around Barcelona.

Site Visits

To onboard ourselves to the topic and context, we organized a walking tour across Barcelona, tracing the city's relationship with water through geography, infrastructure, and time. The tour explored key themes including flooding, water as a resource, supply and wastewater systems, and industrial use of rivers, landscapes, and groundwater.

We began on Las Ramblas, now one of the city's busiest tourist streets but originally a riverbed just outside the Roman city walls around 20 AD. The stream carried water from the Collserola mountains to the sea, aiding drainage during heavy rains. By the 12th century, as the city expanded, the stream was channeled and the area paved to create a promenade. With the eventual removal of the city walls, diverting water from the city center became a critical concern, prompting the development of new flood management strategies.

![]()

Map by Nicolas Tindal (1687-1774) - http://www.swaen.com/antique-map-of.php?id=5920, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25804168

Next, we moved through El Gòtic (the Gothic Quarter), where remnants of Roman aqueducts still stand. These ancient infrastructures once brought water from the mountains into the city to supply public and private baths, fountains, and early sewage systems.

![]()

![]()

The walk continued to Rec Comtal, a medieval-era irrigation channel that remained active into the 19th century. It distributed water across the city and powered flour mills owned by the county, exemplifying the integration of water infrastructure with economic activity.

The final stop was at the Besòs River, on the northeastern edge of the city. Once central to Barcelona’s industrial development, the river became heavily polluted due to its proximity to factories and dense housing. In recent decades, however, the Besòs river has undergone a significant ecological restoration and is now a site of recreation, biodiversity, and sustainable urban planning.

We began on Las Ramblas, now one of the city's busiest tourist streets but originally a riverbed just outside the Roman city walls around 20 AD. The stream carried water from the Collserola mountains to the sea, aiding drainage during heavy rains. By the 12th century, as the city expanded, the stream was channeled and the area paved to create a promenade. With the eventual removal of the city walls, diverting water from the city center became a critical concern, prompting the development of new flood management strategies.

Map by Nicolas Tindal (1687-1774) - http://www.swaen.com/antique-map-of.php?id=5920, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25804168

Next, we moved through El Gòtic (the Gothic Quarter), where remnants of Roman aqueducts still stand. These ancient infrastructures once brought water from the mountains into the city to supply public and private baths, fountains, and early sewage systems.

The walk continued to Rec Comtal, a medieval-era irrigation channel that remained active into the 19th century. It distributed water across the city and powered flour mills owned by the county, exemplifying the integration of water infrastructure with economic activity.

The final stop was at the Besòs River, on the northeastern edge of the city. Once central to Barcelona’s industrial development, the river became heavily polluted due to its proximity to factories and dense housing. In recent decades, however, the Besòs river has undergone a significant ecological restoration and is now a site of recreation, biodiversity, and sustainable urban planning.

Students Work

Authorship of the work within this archive lies with the students.

Water is Us

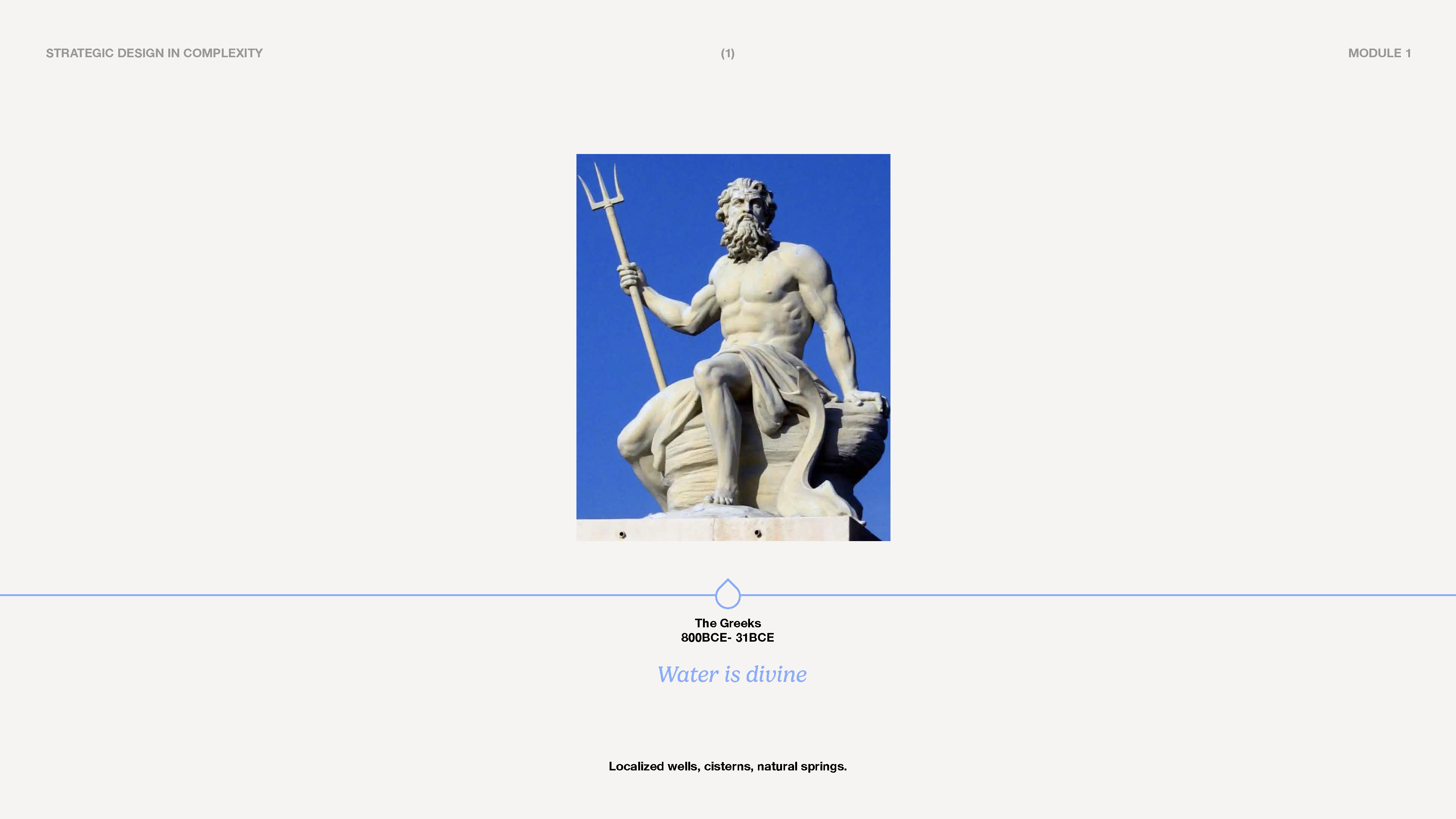

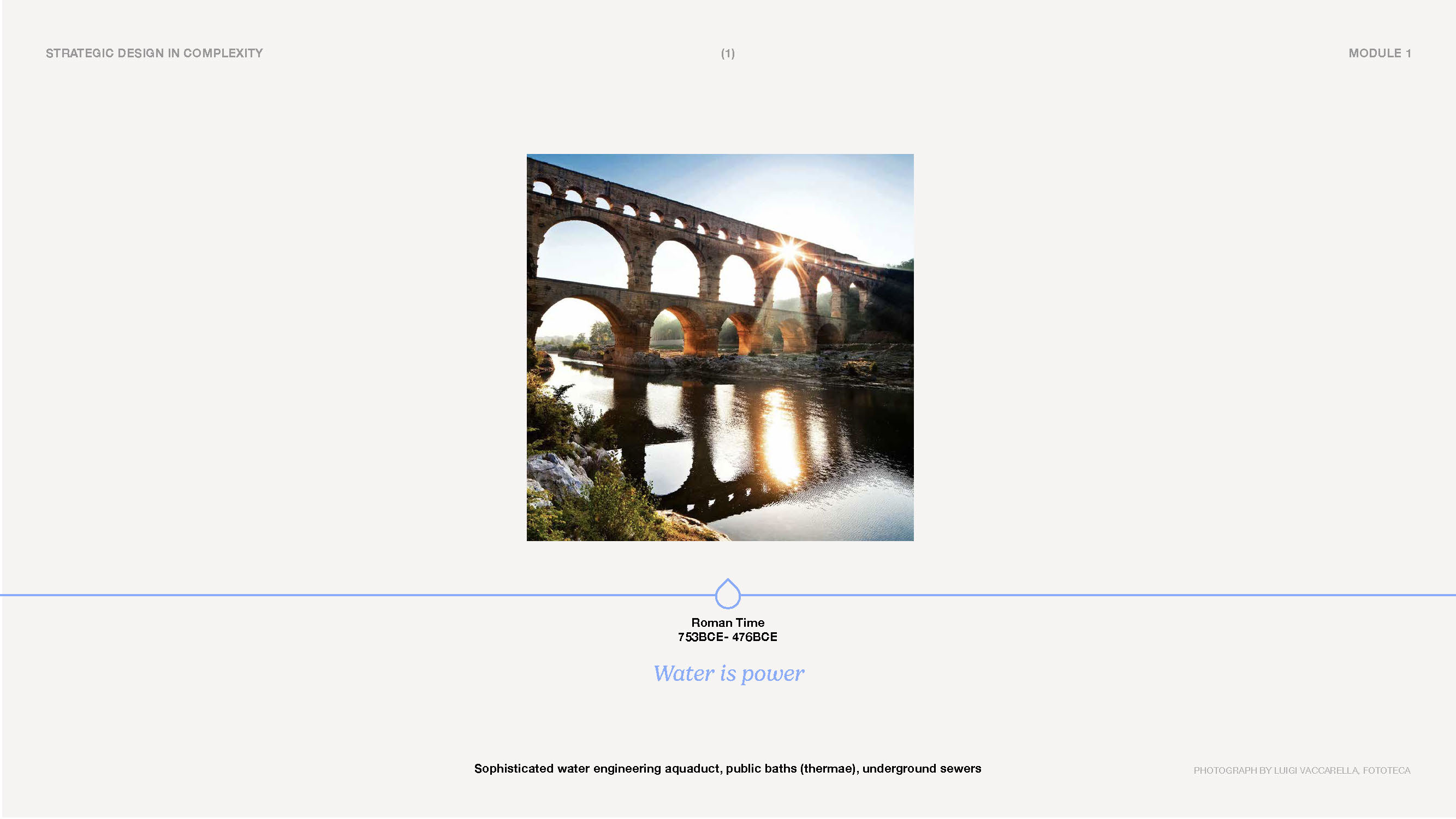

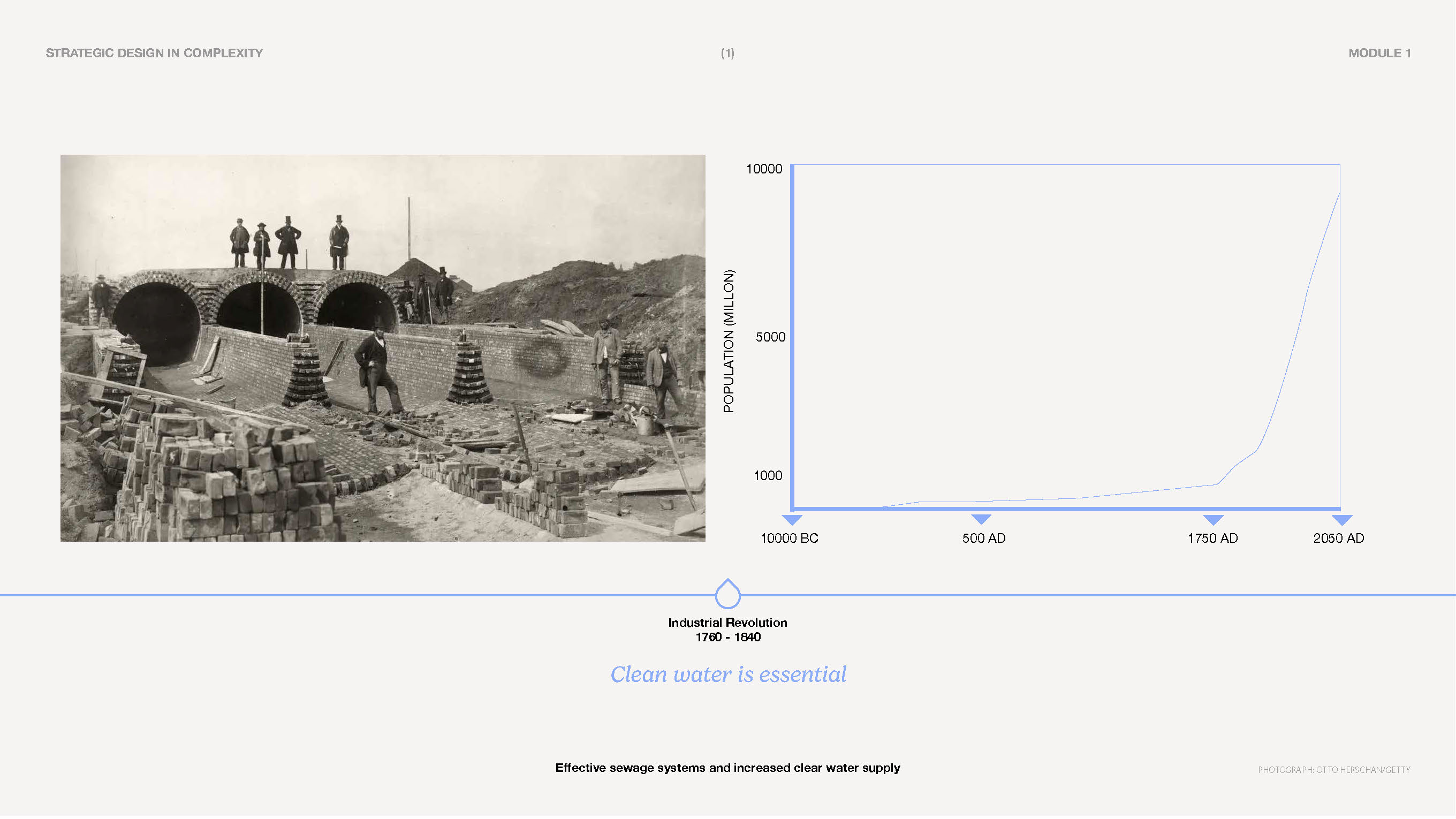

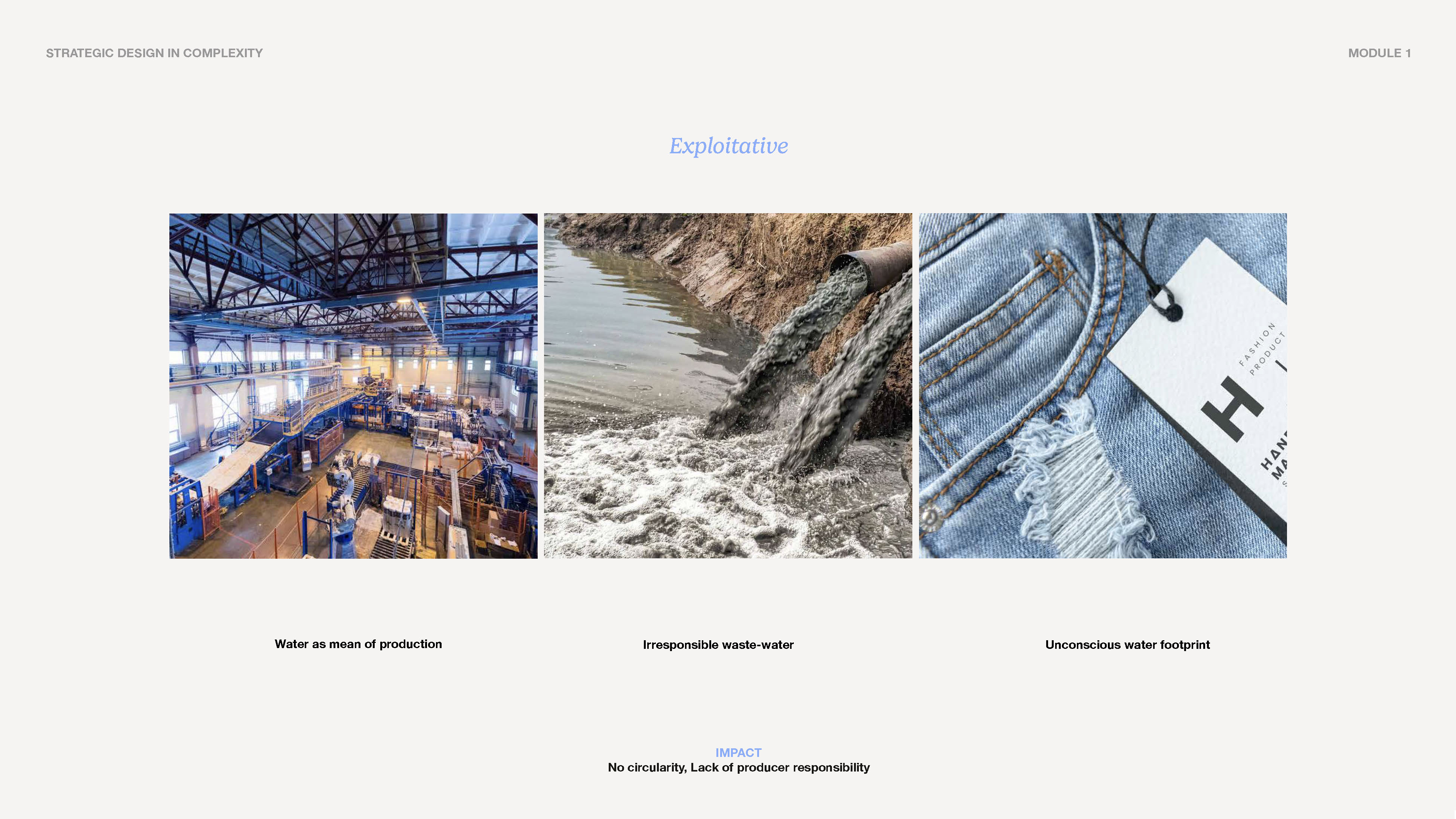

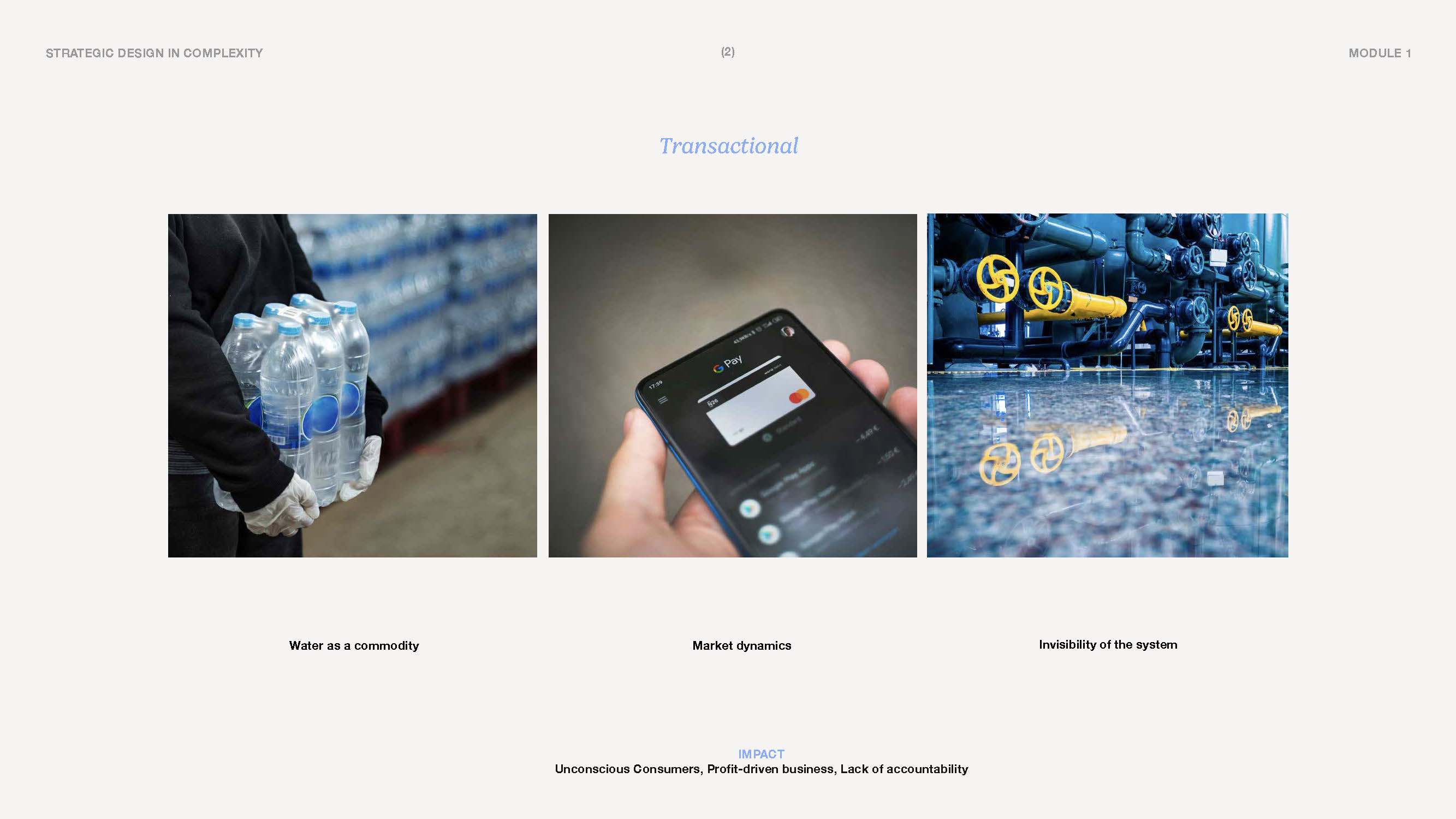

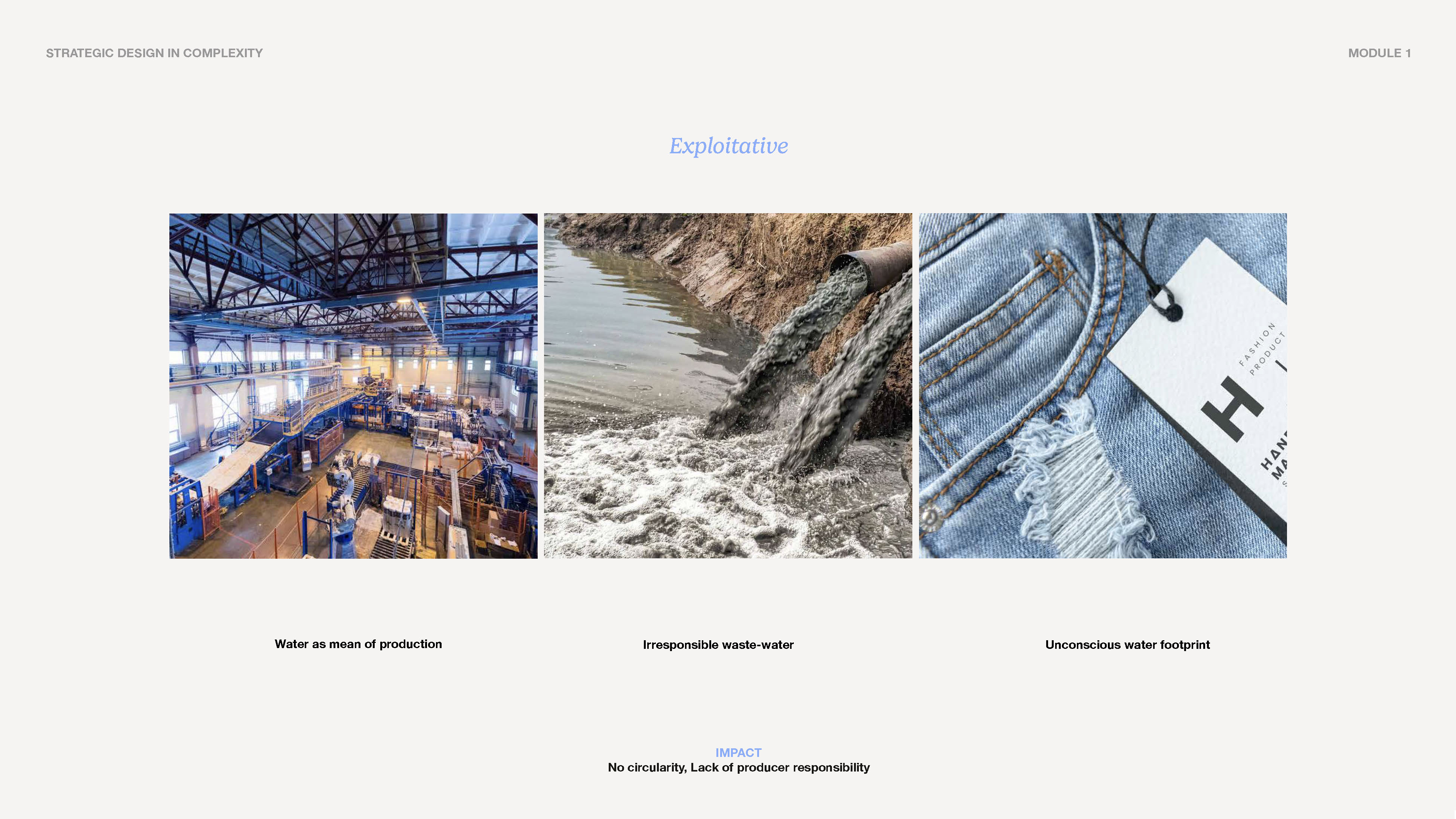

This project examines the evolving human relationship with water, tracing historical perceptions ranging from the divine and powerful to the dangerous and commodified. In contemporary contexts, water is primarily treated as a finite economic resource and a driver of growth. Recurrent droughts and extreme weather events in Catalonia prompted a critical reflection on these prevailing views, in search of more sustainable, long-term approaches.

The research delves into the root causes of drought and the mental models that shape how water is managed. It reveals how institutions, industries, and individuals have historically governed water based on self-interest, reinforcing a narrative of human dominion over the entire water cycle.

To challenge this paradigm, the project proposes a series of systemic interventions aimed at shifting from an extractive, ownership-based mindset—"water is ours"—toward a relational, restorative one—"water is us." These interventions are designed to loosen entrenched structures and open pathways for collective stewardship, emphasizing interdependence, care, and equity in how water is valued and managed.

The research delves into the root causes of drought and the mental models that shape how water is managed. It reveals how institutions, industries, and individuals have historically governed water based on self-interest, reinforcing a narrative of human dominion over the entire water cycle.

To challenge this paradigm, the project proposes a series of systemic interventions aimed at shifting from an extractive, ownership-based mindset—"water is ours"—toward a relational, restorative one—"water is us." These interventions are designed to loosen entrenched structures and open pathways for collective stewardship, emphasizing interdependence, care, and equity in how water is valued and managed.

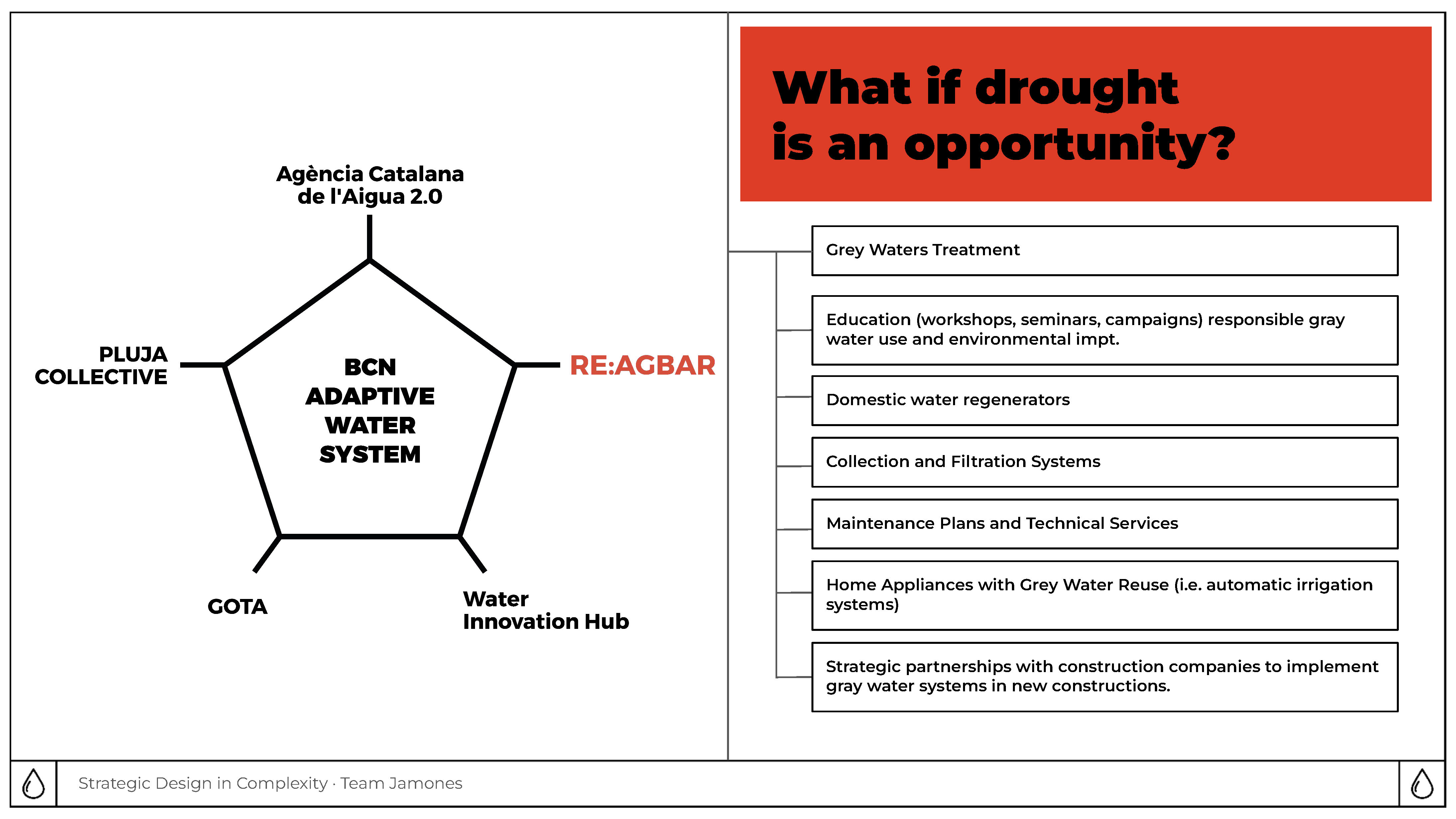

Barcelona, We Need to Talk!

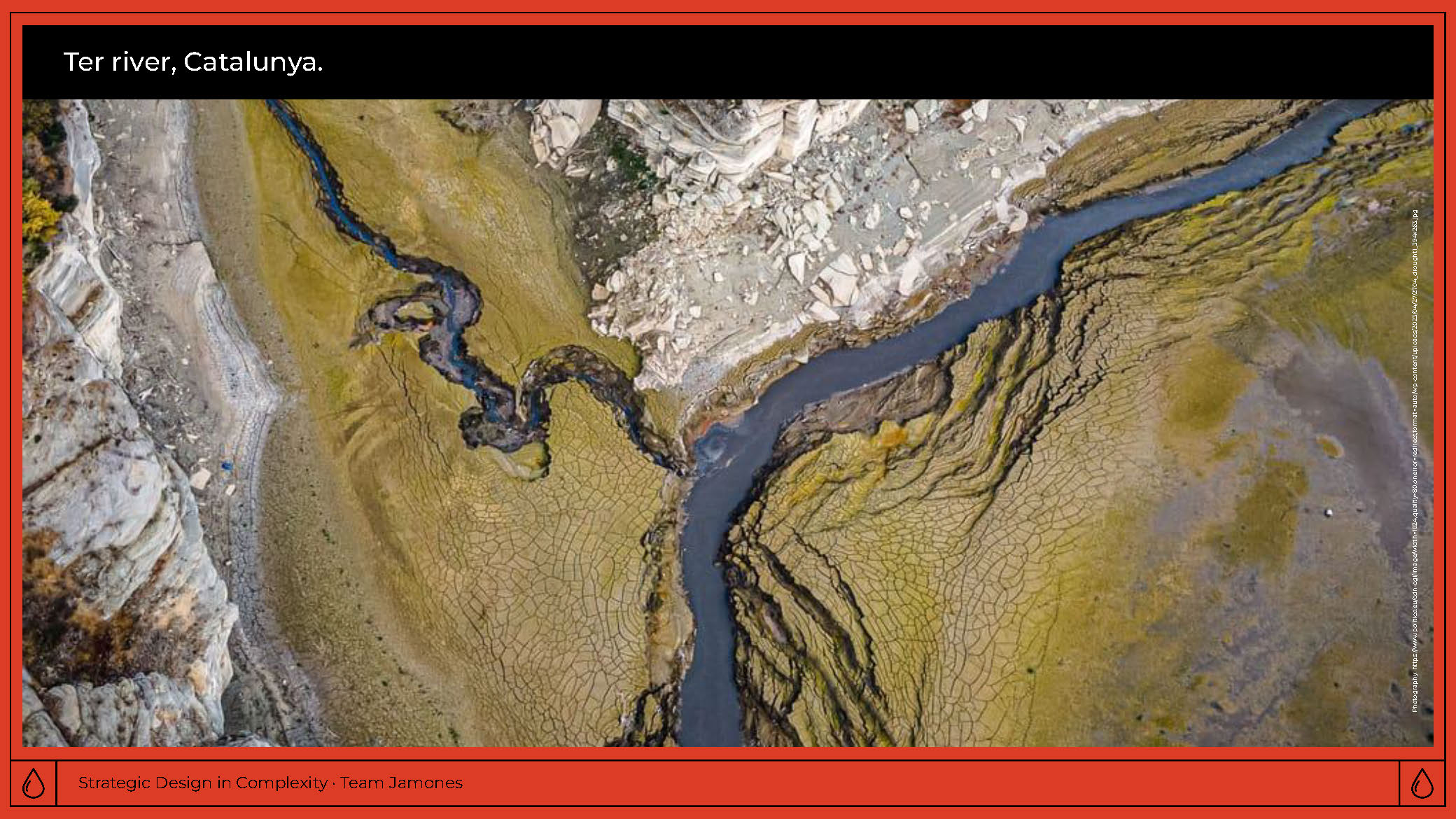

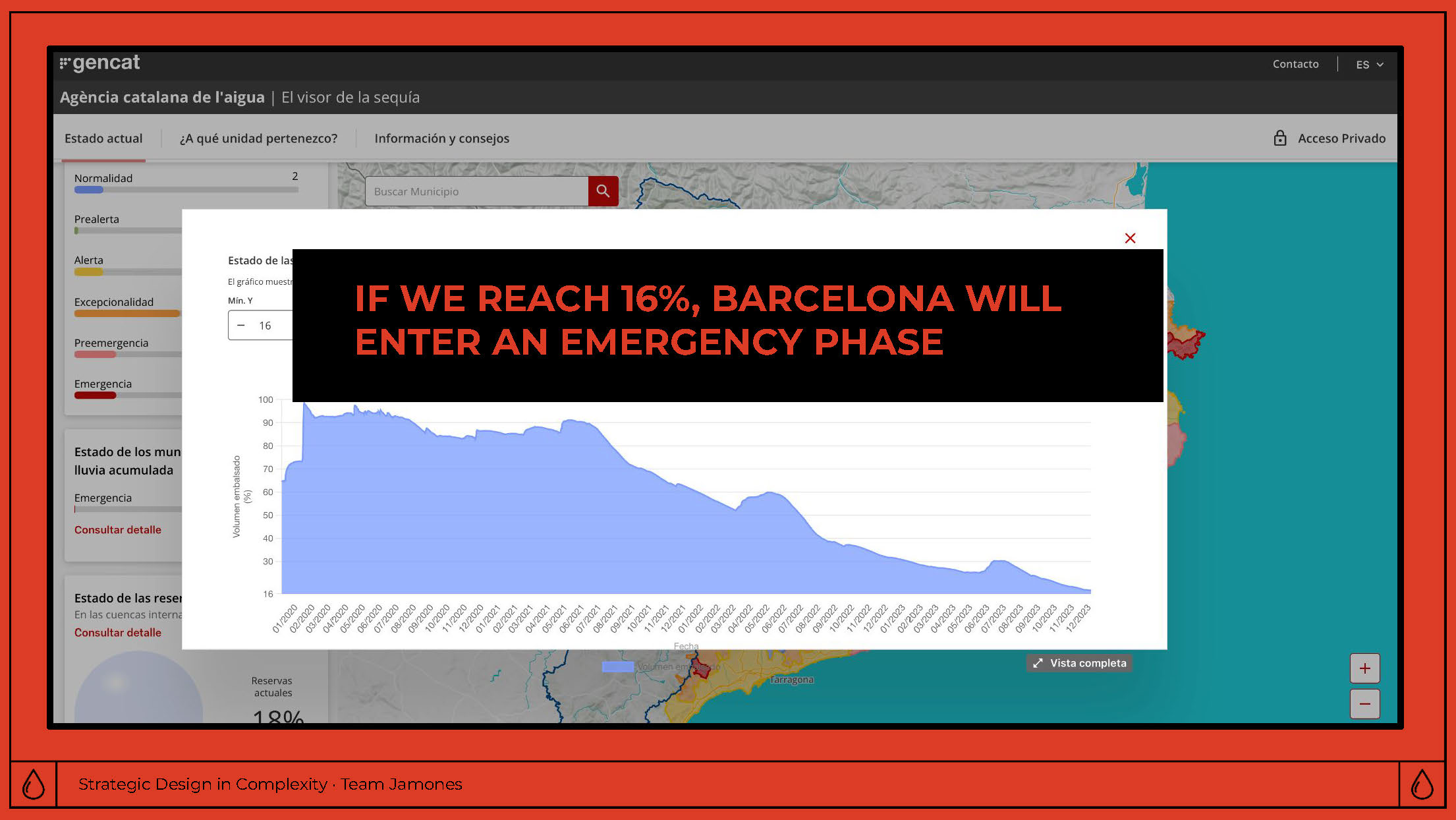

This project investigates the escalating water challenges in Barcelona amid growing concerns of a prolonged drought. During the course of development, the city entered a pre-emergency phase, signaling the increasing severity of its water crisis. Research highlighted the looming threat of a potential “Day Zero,” when municipal water supplies could be exhausted.

As shortages intensify, residents are experiencing increased financial pressure. Government responses have largely been short-term and reactive—emergency measures such as importing water by ship and limited investment in desalination have offered only temporary relief rather than addressing the root causes.

Barcelona’s water management system is characterized by a lack of long-term planning and is hindered by political fragmentation. This disjointed governance structure and narrow planning horizon exacerbate the crisis, with water remaining a low political priority. Without a cohesive, forward-looking strategy, the risk of resource depletion continues to grow.

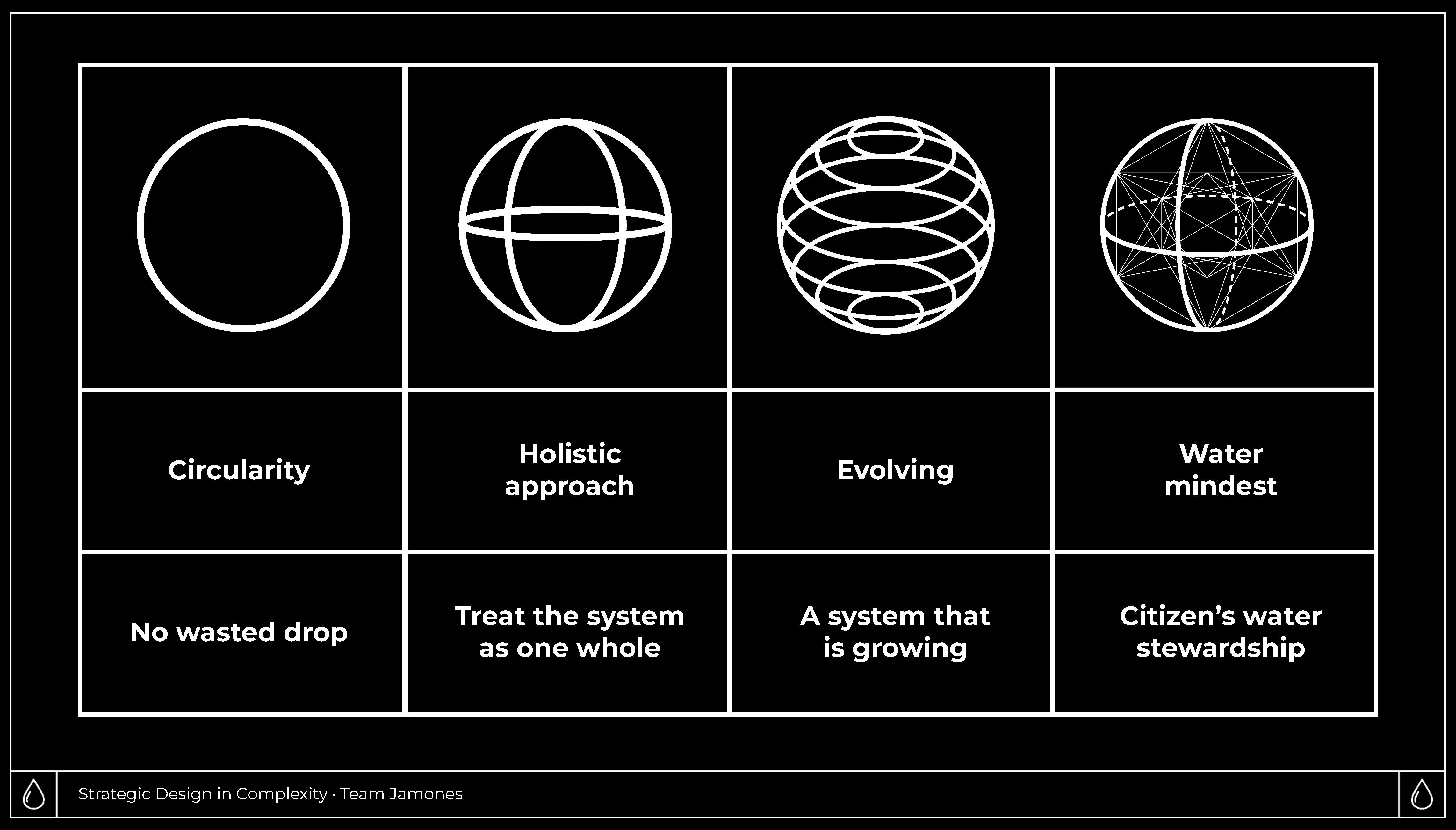

In response, the project proposes a framework based on intentionality, transparency, adaptability, and water-centricity. These principles inform a vision for a sustainable and resilient water future. The proposed interventions target cultural engagement, technological innovation, economic incentives, and regulatory reform—designed to foster systemic change and enable collaborative, long-term stewardship of water resources.

As shortages intensify, residents are experiencing increased financial pressure. Government responses have largely been short-term and reactive—emergency measures such as importing water by ship and limited investment in desalination have offered only temporary relief rather than addressing the root causes.

Barcelona’s water management system is characterized by a lack of long-term planning and is hindered by political fragmentation. This disjointed governance structure and narrow planning horizon exacerbate the crisis, with water remaining a low political priority. Without a cohesive, forward-looking strategy, the risk of resource depletion continues to grow.

In response, the project proposes a framework based on intentionality, transparency, adaptability, and water-centricity. These principles inform a vision for a sustainable and resilient water future. The proposed interventions target cultural engagement, technological innovation, economic incentives, and regulatory reform—designed to foster systemic change and enable collaborative, long-term stewardship of water resources.

Barcelona Design Week

What began as a course project running from October 2023 to February 2024 quickly evolved into a sustained commitment beyond the academic program. Following the studio, the students and myself continued working together, pursuing grant opportunities, and building relationships with public institutions and industry partners.

As part of our research and ongoing stakeholder engagement during the project, we established a dialogue with the curation team of Barcelona Design Week. Given the region’s escalating drought crisis, we proposed centering this year’s theme around water, a proposal that was ultimately adopted.

As a result, we were invited to present a series of exhibitions and public engagements, each exploring a distinct facet of design’s relationship with water:

These interventions invited public engagement, sparked meaningful dialogue, and opened new pathways for research and collaboration. The community response—rich in reflection, curiosity, and even emotion—underscored the resonance of the work.

![]()

As part of our research and ongoing stakeholder engagement during the project, we established a dialogue with the curation team of Barcelona Design Week. Given the region’s escalating drought crisis, we proposed centering this year’s theme around water, a proposal that was ultimately adopted.

As a result, we were invited to present a series of exhibitions and public engagements, each exploring a distinct facet of design’s relationship with water:

- Talk at Barcelona Design Week: A conversation reframing water not as a resource at humanity’s disposal, but as a living system of which humans are a part. The talk invited a shift in perspective: "water isn’t ours; water is us."

- Bet of the Future: A collection of speculative objects designed to challenge dominant mental models and explore ecological futures.

- Amor Sec: An immersive installation placing participants in a world without water, prompting reflection on urgency, loss, and interdependence.

- H2Oh!: A data-driven visualization of domestic water usage, aimed at fostering everyday awareness and stewardship.

These interventions invited public engagement, sparked meaningful dialogue, and opened new pathways for research and collaboration. The community response—rich in reflection, curiosity, and even emotion—underscored the resonance of the work.

Amor Sec

A street installation inviting visitors to engage in a future Barcelona without water, prompting reflection and creating messages – in the form of postcards – to themselves and their relationship with water.

Student designed exhibitions presented at Barcelona Design Week 2024

Bet of the Future

This interactive installation explored four future-oriented mindsets, envisioning provocative objects from the future to spark new dialogues around sustainable water use across multiple stakeholders at a time.

H2Oh!

An interactive installation to raise awareness and educate residents about our day-to-day water consumption in each activity at home.

References

The Barcelona Climate Plan 2018-2030 as one document sets out some goals in response to the above questions, that the city should by now be on the verge of seeing come to fruition (or not), including sewer management, coastline management, drought protocols, urban resilience, and green infrastructure.

Ajuntament de Barcelona. Taking Care of Water. On 15 January 2020, the city of Barcelona declared a climate emergency and accelerated a series of changes involving all players in the city.

Circle of Blue. A Decade After Barcelona’s Water Emergency, Drought Still Stalks Spain. Includes further readings and resources

Stephen Burgen. Catalonia’s farmers face threat of drought … and a plague of hungry rabbits. The Guardian. April 2023.

Guy Hedgecoe. Climate change: Catalonia in grip of worst drought in decades. The BBC. April 2023.

Zia Weise and Antonia Zimmermann. Europe’s next crisis: Water. Politico. April 2023.

Council of Ministers. The Government approves the Third Cycle Hydrological Plans to modernize the management of water resources until 2027. January 2023.

Guillem Costa. Catalonia further restricts water for agricultural, industrial and urban use. El Periodico. February 2023.

The Barcelona Climate Plan 2018-2030 as one document sets out some goals in response to the above questions, that the city should by now be on the verge of seeing come to fruition (or not), including sewer management, coastline management, drought protocols, urban resilience, and green infrastructure.

Ajuntament de Barcelona. Taking Care of Water. On 15 January 2020, the city of Barcelona declared a climate emergency and accelerated a series of changes involving all players in the city.

Circle of Blue. A Decade After Barcelona’s Water Emergency, Drought Still Stalks Spain. Includes further readings and resources

Stephen Burgen. Catalonia’s farmers face threat of drought … and a plague of hungry rabbits. The Guardian. April 2023.

Guy Hedgecoe. Climate change: Catalonia in grip of worst drought in decades. The BBC. April 2023.

Zia Weise and Antonia Zimmermann. Europe’s next crisis: Water. Politico. April 2023.

Council of Ministers. The Government approves the Third Cycle Hydrological Plans to modernize the management of water resources until 2027. January 2023.

Guillem Costa. Catalonia further restricts water for agricultural, industrial and urban use. El Periodico. February 2023.

Index