DESIGN BEYOND CRISIS

COURSE

Design Beyond Crisis IDISC1544

Interdisciplinary Studies

Studio Course

Spring 2022

Center for Complexity

Rhode Island School of Design

︎︎︎RISD Center for Complexity

Interdisciplinary Studies

Studio Course

Spring 2022

Center for Complexity

Rhode Island School of Design

︎︎︎RISD Center for Complexity

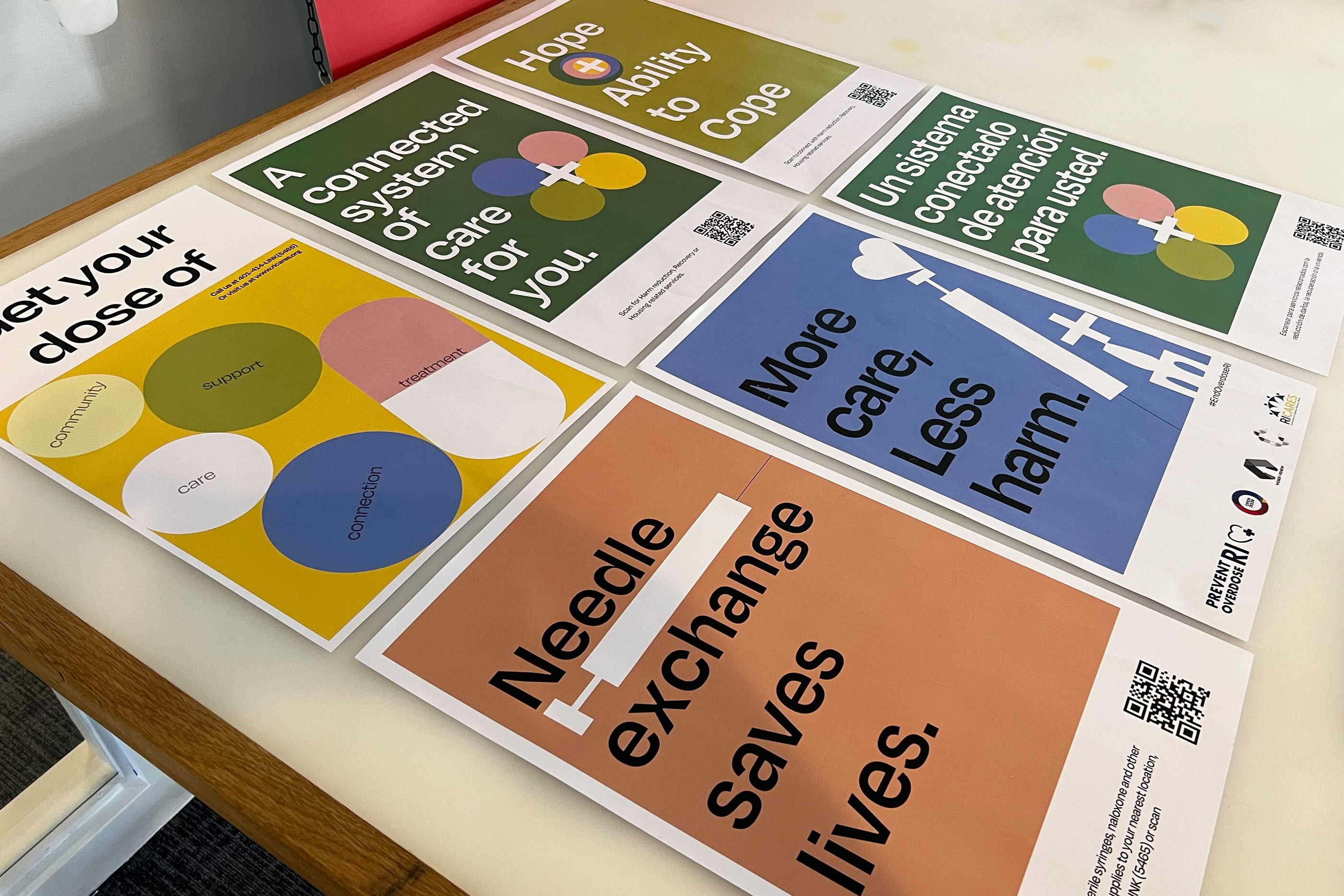

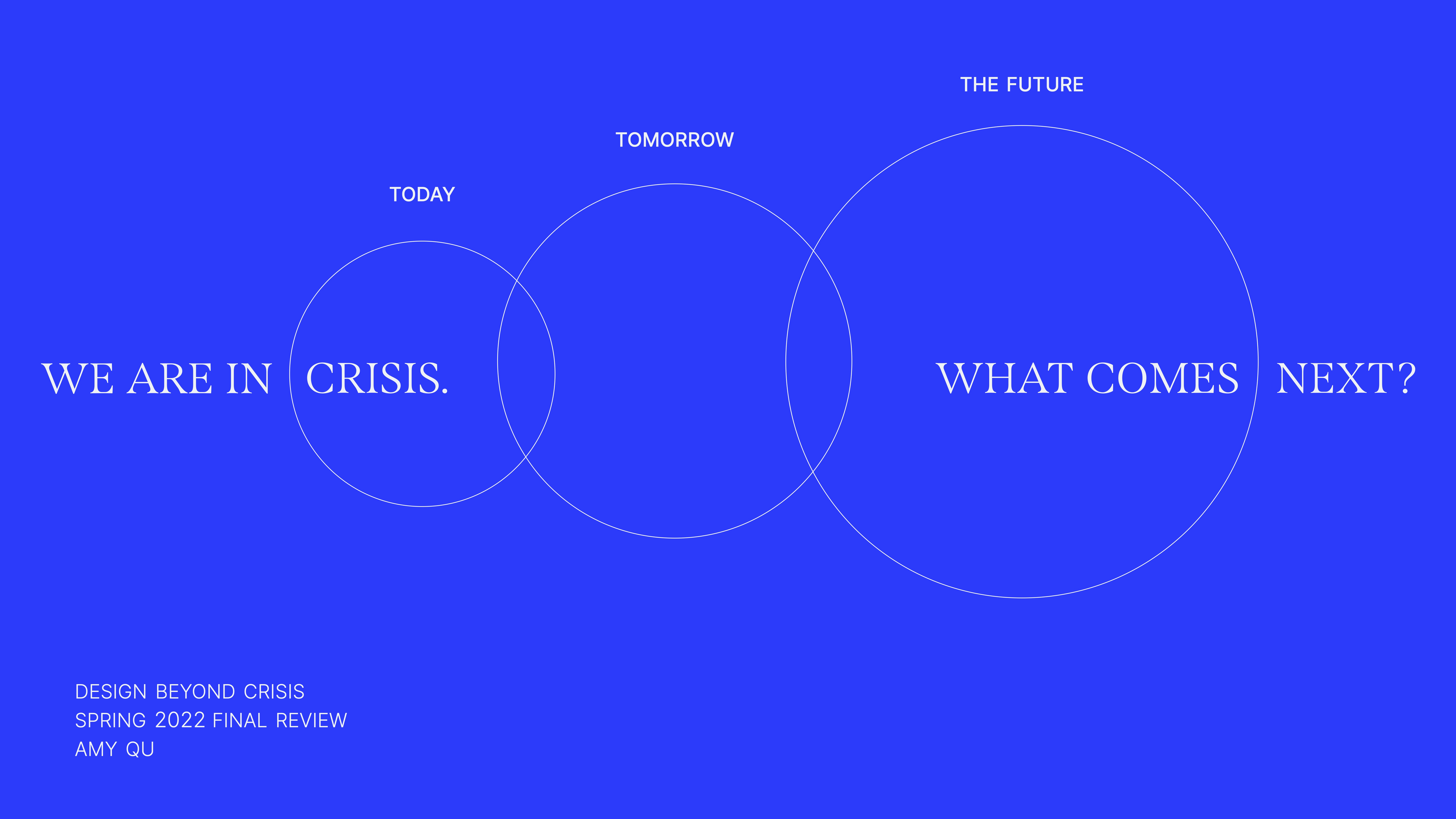

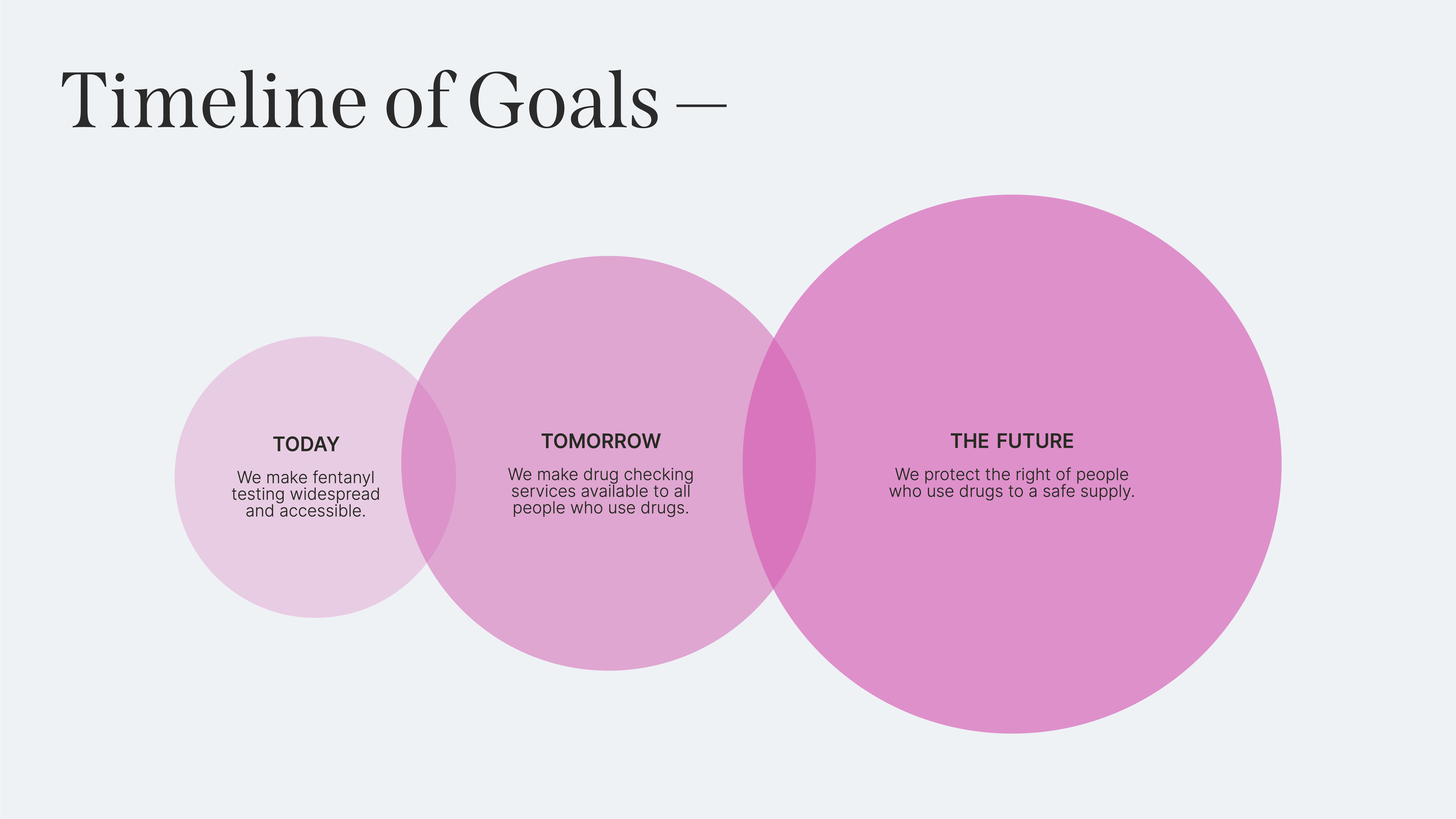

On July 7, 2021, legislation was signed authorizing a two-year pilot program to prevent drug overdoses through the establishment of harm reduction centers in Rhode Island — a first in the United States. The law and regulations set minimum criteria that a harm reduction center must operate within. Between regulation and implementation, there lies a host of design decisions that span disciplines and scale. These will have a profound impact on the health and wellbeing of all who occupy the site. They must not be left to chance.

This interdisciplinary studio provided students from interior architure and industrial design the opportunity to explore and shape the material realization of an inclusive and humanistic system of care. Building on the Center for Complexity’s multi-year engagement with the overdose crisis, this studio connected students to an active community of stakeholders, explored the history of harm reduction centers and similar sites, interrogated the considerations (social, material, spacial, experiential) that shape their design, and confront the context-specific forces that will determine the outcomes.

This interdisciplinary studio provided students from interior architure and industrial design the opportunity to explore and shape the material realization of an inclusive and humanistic system of care. Building on the Center for Complexity’s multi-year engagement with the overdose crisis, this studio connected students to an active community of stakeholders, explored the history of harm reduction centers and similar sites, interrogated the considerations (social, material, spacial, experiential) that shape their design, and confront the context-specific forces that will determine the outcomes.

Alongside the students developing individual projects in response to the studio brief throughout the semester, we designed moments of collective making and research to build a shared knowledge amongst the studio cohort. To begin the course, we asked students to conduct a deep dive exploration on stigma and aesthetics.

Students explored how stigma and the aesthetics of drugs, drug use, and addiction is present, percieved, and communicated in our culture. They analyzed the tactics/strategies/dynamics operative in the evidence they collected. Applying these same strategies, they applied them to other forms of “addiction” (ie. coffee, soda, cellphones).

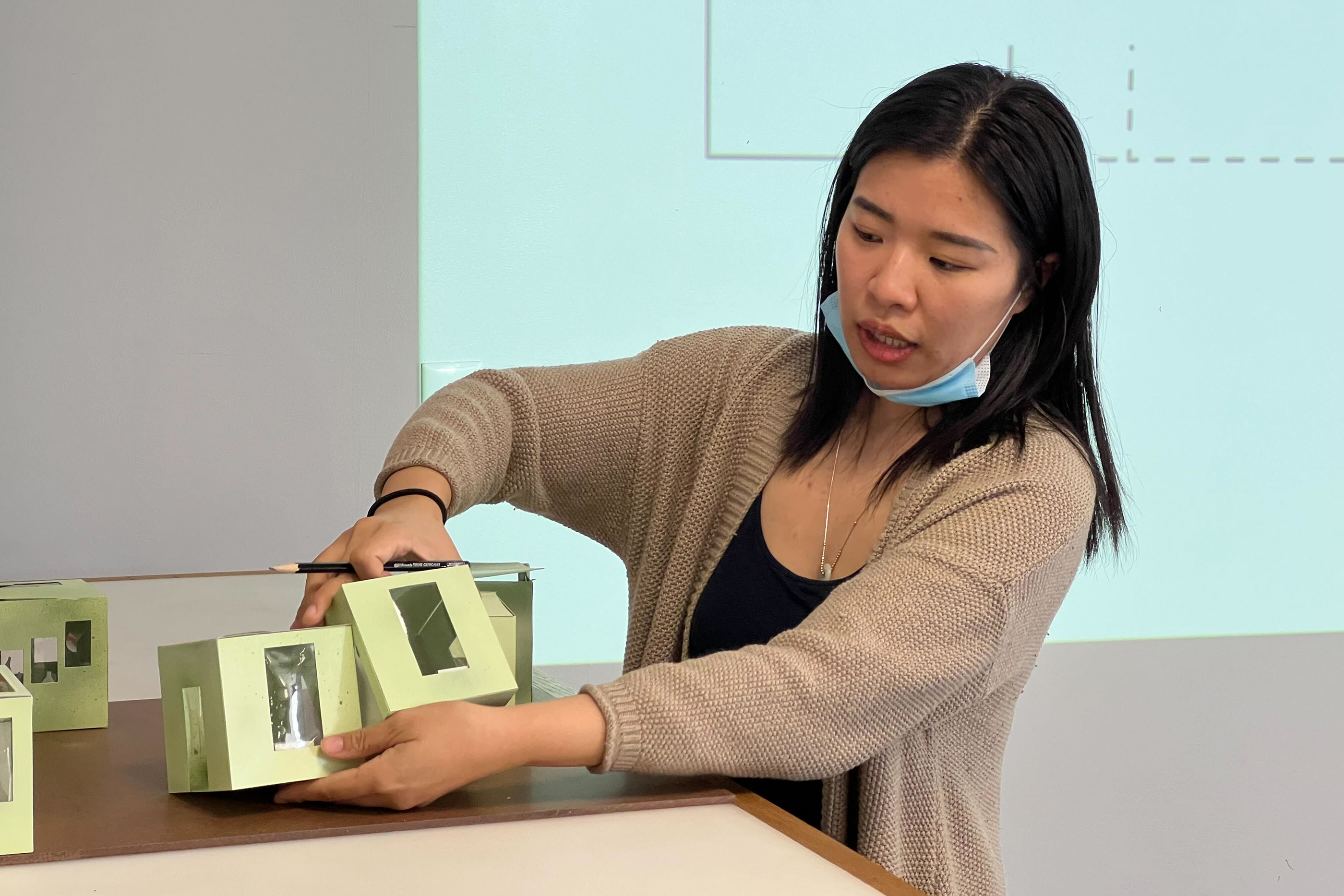

Design Charette

Halfway through the semester we organized a 1-day design charette for the students to collaborate and generate collective knowledge on a specific question.

What is a design charette?

“The term ‘charette’ evolved from a pre-1900 exercise at the École des Beaux Arts in France. Architectural students were given a design problem to solve within an allotted time. When that time was up, the students would rush their drawings from the studio to the École in a cart called a charrette. Students often jumped in the cart to finish drawings on the way. The term evolved to refer to the intense design exercise itself. Today it refers to a creative process akin to visual brainstorming that is used by design professionals to develop solutions to a design problem within a limited timeframe.” (Carnegie Mellon University Libraries)

Design Charette Brief

A great deal of thought is being given to the location of harm reduction centers and their interior. In consultation with visiting expert Dr. Jon Soske, we decided to turn our attention to the threshold between those two factors – the design of the entrance and exit. What is the experience, considerations, and design of the pre and post?

The challenge is to balance two manifestations of stigma against people who use drugs. First, the idea that they are not welcome and the fact that they have arrived as PWUD is shameful. We have no place. While this is perhaps unintentional, this is reflected in the architectural idiom of methadone clinics, treatment programs, recovery centers, 12 step recovery meetings—anonymous, unmarked, off the side entrance, grey, blacked out windows, underground in every sense of the word. This is the architecture of personal defeat, of utter humiliation—only the defeated would pass through these unmarked doors and into buildings, whose internal composition, no "ordinary" person will ever see. To walk into these spaces, at least visually, but also affectively, is to be cut off from the world. The outside of BHLink is a perfect example.

![]() BHLink Entrance. Source: maps.google.com

BHLink Entrance. Source: maps.google.com

Second, there is a genuine functional purpose to this idiom: it is meant to protect people from identification and descrimination. If I am seen entering an OPS, let alone photographed, that could cost me my job, my family, my reputation, my licenses.... In the United States, there are far fewer protections for people who seek SUD treatment than in Canada and none for people who use drugs.

This is the double-bind that stigma imposes at the entrance: how do we welcome people, and convince them that they are entering a space of love and support, while at the same time offering them safety and protection? The challenge is both sensory and immediately functional in terms of personal security, and strikes at an ideologically infused architectural idiom that has accrued around the institutions that we have created.

The challenge is to balance two manifestations of stigma against people who use drugs. First, the idea that they are not welcome and the fact that they have arrived as PWUD is shameful. We have no place. While this is perhaps unintentional, this is reflected in the architectural idiom of methadone clinics, treatment programs, recovery centers, 12 step recovery meetings—anonymous, unmarked, off the side entrance, grey, blacked out windows, underground in every sense of the word. This is the architecture of personal defeat, of utter humiliation—only the defeated would pass through these unmarked doors and into buildings, whose internal composition, no "ordinary" person will ever see. To walk into these spaces, at least visually, but also affectively, is to be cut off from the world. The outside of BHLink is a perfect example.

BHLink Entrance. Source: maps.google.com

BHLink Entrance. Source: maps.google.com

Second, there is a genuine functional purpose to this idiom: it is meant to protect people from identification and descrimination. If I am seen entering an OPS, let alone photographed, that could cost me my job, my family, my reputation, my licenses.... In the United States, there are far fewer protections for people who seek SUD treatment than in Canada and none for people who use drugs.

This is the double-bind that stigma imposes at the entrance: how do we welcome people, and convince them that they are entering a space of love and support, while at the same time offering them safety and protection? The challenge is both sensory and immediately functional in terms of personal security, and strikes at an ideologically infused architectural idiom that has accrued around the institutions that we have created.

– Dr. Jon Soske

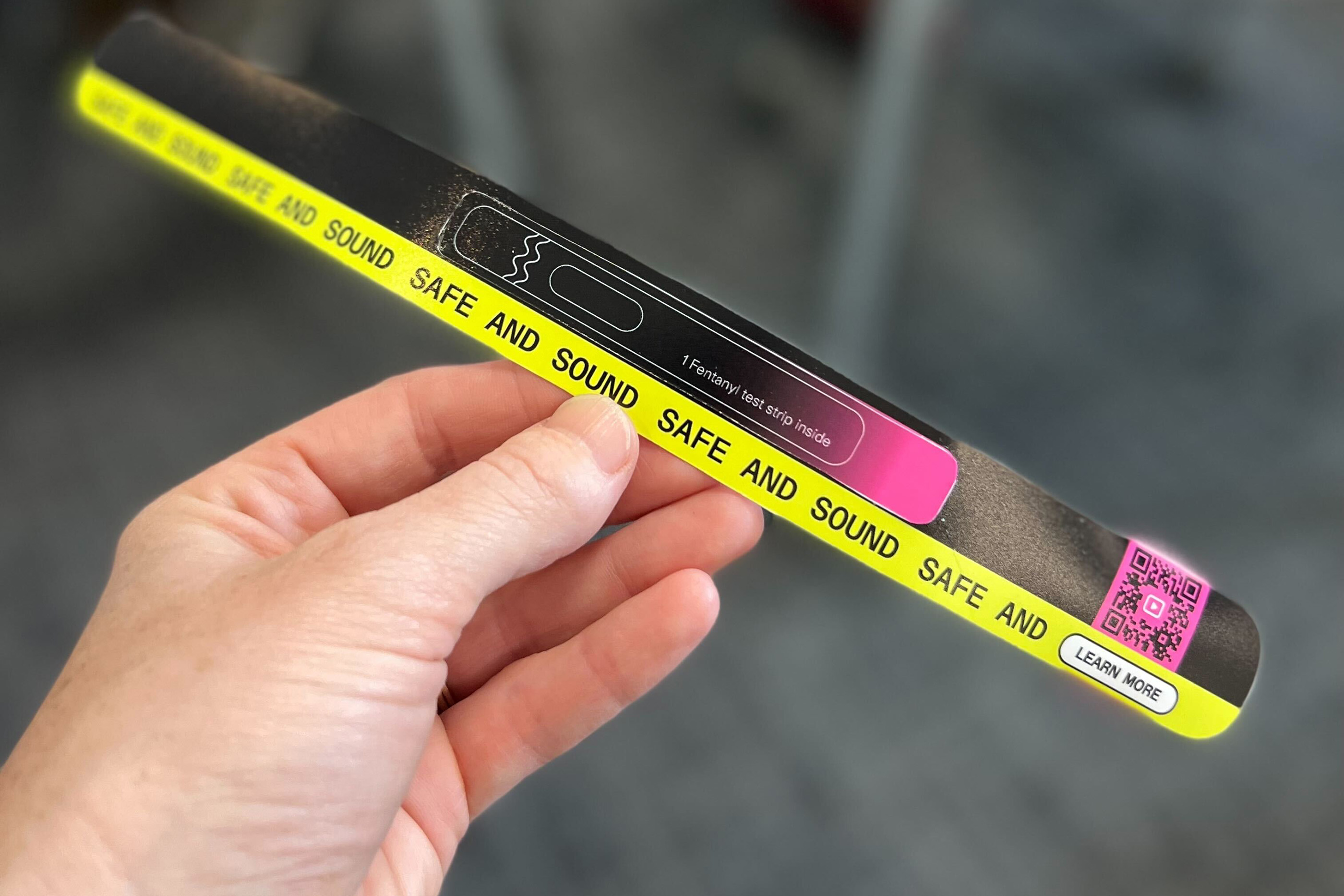

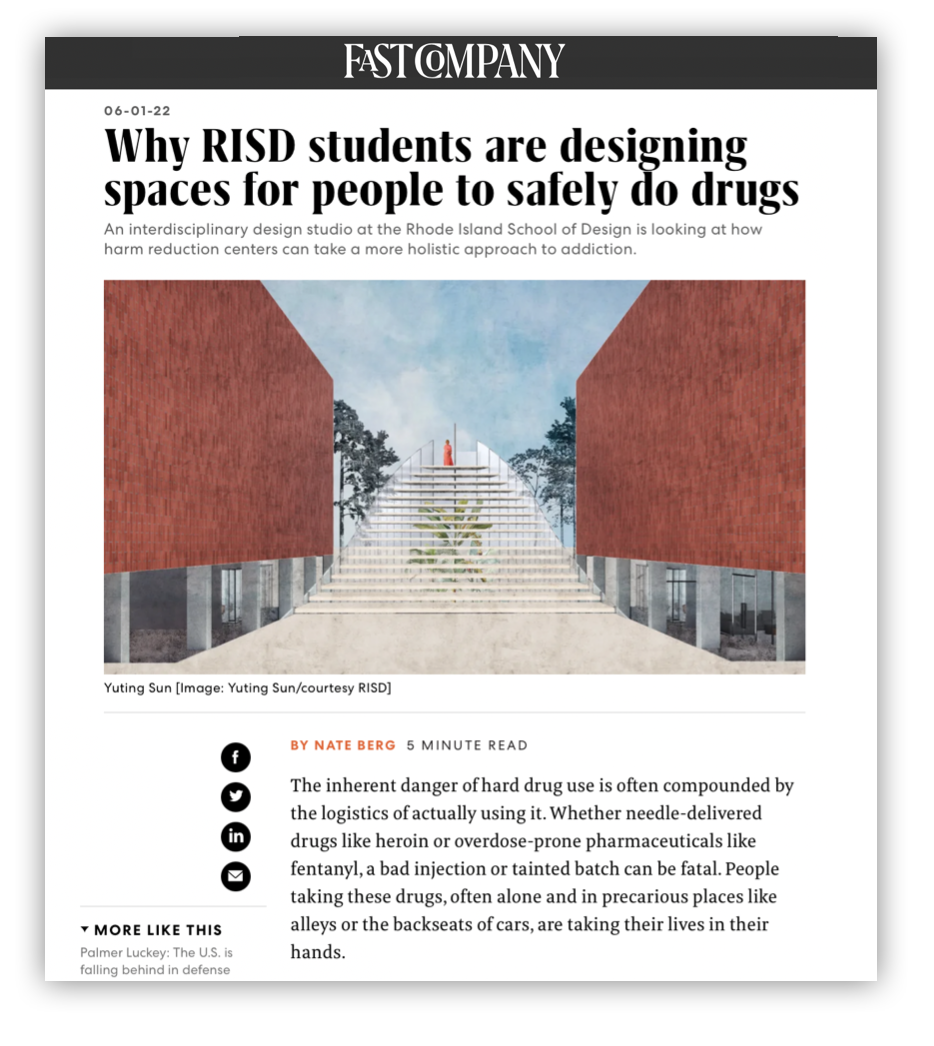

Student projects from this course have been recognized by numerous media outlets such as Fast Company, The Boston Globe, and The Providence Journal. Some projects will continue to be developed post-studio course.

Related Publications

Berg, Nate. “Why RISD students are designing spaces for people to safely do drugs”, Fast Company, June 1, 2022.

Gagosz, Alexa. “How artists could play a role in harm reduction centers”, Boston Globe, May 16, 2022.

Mulvaney, Katie. “Innovative RISD projects tackle opioid crisis and stigma through design”, Providence Journal, May 28, 2022.

Mulvaney, Katie. “Replace stigma with compassion: RISD students reimagine better approaches to drug addiction”, Providence Journal, May 15, 2022.

Index